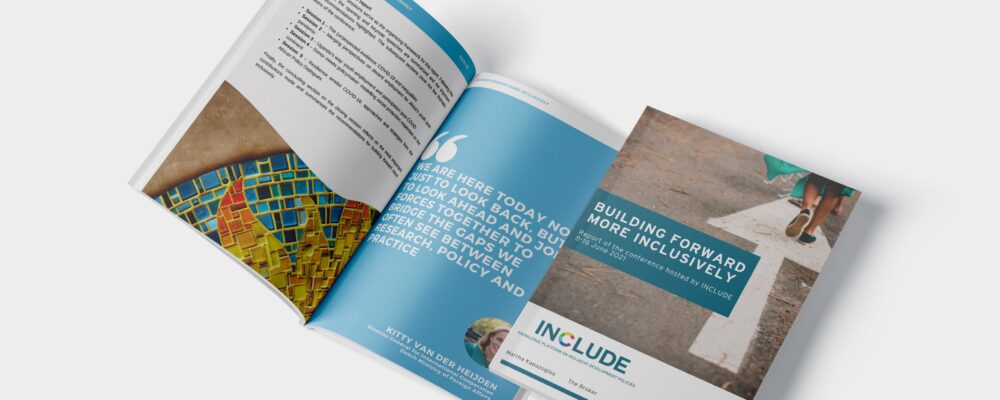

High levels of economic growth are not sufficient to reach the bottom 40%. Despite this being an increasingly accepted view, policies to promote inclusiveness often remain empty shells as existing power structures are unchallenged. If we want to reach the bottom of the pyramid, we shouldn’t shy away from politics!

That is the main conclusion that can be drawn from the discussion meeting ‘Inclusive Development in Practice’, held at the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) last Wednesday, 18 February. Like many other institutions, including the OECD and the IMF, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, is increasingly treating high levels of inequality as a risk. Reina Buijs, Deputy Director-General for International Cooperation, voiced this change in approach by stressing that ‘Inclusive development is a sine qua non for sustainable development. We know the theories, but we need to put them into practice’.

Jos Verbeek, Lead Economist and Senior Advisor at the World Bank and keynote speaker at the meeting, emphasized the importance of inclusive growth in creating jobs and income stability for the poor and the lower middle class. However, it is important to realize that there are no quick fixes for these issues. That is why there is a great need for more detailed knowledge about which policies work in which contexts. Moreover, tackling inequality with redistributive measures only is certainly not enough. It requires a change in existing governance structures and above all the political and economic incentives to bring about that change.

Growth is not enough

While, during the 1990s, the World Bank equated economic growth with development, it has now come to realize that ‘growth alone is not enough’. Rather than focusing on macroeconomic indicators, the Bank now aims to increase the income of the bottom 40%. Despite this being a welcome change in the World Bank’s focus, promoting policies aimed at reducing poverty among the bottom-40 certainly is not the same as truly tackling income inequality.

Moreover, the Bank’s new Global Monitoring Report still reinforces the belief that growth is key to creating jobs, which in turn are necessary to making sure that those at the bottom of the pyramid are included in sharing the prosperity generated by economic growth. As Verbeek argued, making sure that people have a job and can benefit from macroeconomic growth requires, according to the World Bank, above all investment in education and social safety nets.

However, by focusing primarily on social redistributive measures, the World Bank shies away from the notion that inequality can only be tackled when economic power structures are changed, both nationally and internationally (for more on this argument, see The Broker’s inequality dossier).

So who should be targeted?

Despite awareness of persisting inequalities, participants from the MFA stressed that the question of who to target creates a dilemma for donor governments: ‘Do we want to invest in the poorest, or in the people with the most potential?’. For foreign investors, investing in lifting large groups of people out of poverty is often seen as more beneficial than targeting small groups. But who then bears the primary responsibility for reaching the most excluded?

This practice of ‘picking the winners’ is a political choice, as Tom van der Lee, Director of Campaigns and Advocacy at Oxfam Novib, rightfully argued. The people that have the most potential economically are often already targeted by national governments. So donors should make sure they invest in those that have not yet been reached and create the economic incentives for national governments to do the same.

Focus on rural

One sector where such incentives would be able to make an impact is agriculture. According to Van der Lee, investments in agriculture generate up to four times the returns of any other type of investment. Moreover, they imply a clear win-win as they address other problems – like the growing demand for food and urbanization – at the same time.

Furthermore, rural areas – where the most excluded generally live – are crucial for ensuring food security. Currently however, agricultural activities in these areas, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, continue to fall woefully short of their productive potential.

Consequently, with agricultural activity being the main source of income for people living in these areas, the yields that the poorest receive are extremely unstable and are insufficient to guarantee a decent standard of living. This causes many people to move to the cities, where they end up in slums and are forced to seek work in the informal sector. Here too, their incomes are unstable and social protection is still lacking.

Focus on healthcare

Another sector with great potential is healthcare. Here, investing in public-private partnerships can likely be a win-win for both businesses and governments.

As Jan-Willem Scheijgrond, Global Head of Government Affairs Business to Government (B2G) at Royal Philips, argued, health crises are the main reasons that families in developing countries fall back into poverty, since they often cannot rely on a social safety net and will take on debt in case of a crisis.

Meanwhile, official development aid can only provide a fraction of the investments needed in healthcare. So in order to leverage their impact, donors and national governments should link up with private companies to meet the ever-growing demand. These companies in turn need to realize that investment in the healthcare sector yields high returns while creating productive jobs and better lives at the same time.

What about politics?

Although there are some good examples of public-private partnerships, the scale on which they are implemented remains quite limited. Moreover, blind trust in private sector involvement overshadows the fact that the problem here is not economic, but political. In the end it has to be the governments, at both national and international level, that need to take responsibility for reducing inequality.

The reason why governments avoid doing this lies not with a lack of institutional capacity, but of political will. This is exemplified most clearly with the issue of taxation. Here, it is not only about building the proper financial infrastructure in countries where it is lacking, but making sure that taxes [are actually paid and??] end up where they should. As Van der Lee said, 21 trillion dollars are still currently being stashed away in tax paradises.

Information is key

For this to happen, according to Peter Lanjouw, professor at the Department of Economics at Free University Amsterdam and former Research Manager at the World Bank, it is essential to have the right information. In order to hold those powerful few at the top of the pyramid accountable for their actions, we need to know how current structures benefit those in power.

Currently however, we know too little about who the rich in developing countries actually are. The same goes for the poor. Despite there being a great deal of interest in country-level data about the most excluded (where do they live? where do they work? why are they excluded?), Lanjouw says that there is not much interest in actually producing these facts. And knowing whether we are actually making any progress towards ending poverty by 2030 requires detailed metrics that can help policymakers to prioritize limited resources.

How to enter open doors

Thus, information is key. For governments, donors and companies to make the right decisions; and also for citizens to hold those in power accountable. The solution must be found in the political nature of the problem. It is about changing the incentives for governments and companies, so that they too benefit from creating more balanced economic relations. Yet, despite some suggestions about the right areas to invest, exactly how these incentives could be created remained an unresolved question during today’s discussion.

The good news is that thinking about equality has evolved, and not only within the World Bank. As Harman Idema, Head of the MFA’s Office for International Cooperation, emphasized ‘the idea that growth is not sufficient for sustainable development is now almost an open door’. The question now is, who has the courage to enter it?