After participating in two events on inequality at the Spring Meetings – Making Growth Work for the Poor and Income Inequality Matters: How to Ensure Economic Growth Benefits the Many and Not the Few, I received a surprising number of emails asking whether my remarks on the importance of addressing rising inequality meant I had abandoned growth as the main priority for developing countries. One thing I certainly took away from this correspondence: Inequality is too complex a phenomenon to address in a brief session at the Spring Meetings.

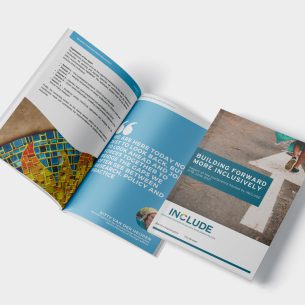

This is why the Institute of Fiscal Studies in London (IFS) has put together an ambitious, multi-disciplinary project, headed by Nobel Prize winner Angus Deaton, the so-called Deaton Review, to understand the multiple aspects of inequality and propose appropriate policies. Pointedly, the project is called “Inequalities in the twenty-first century” – note the plural. The multi-disciplinary project brings together experts from Economics, Political Science, Sociology, and Public Health aiming at a comprehensive yet nuanced, and most importantly balanced discussion of “inequality.”

Recognizing the complexity of the issues, the project has a four-year timeline. I hope by its completion, we will have a better grasp of why “inequality” (I am going back to the singular following convention) is such an important concern today, both among policy makers and the public, and what we can do to address it. But, for those of you who may not want to wait that long, here are my two cents.

Both theoretically and empirically, we expect growth and changes in the income distribution to go hand in hand. But this positive relationship neither means an increase in income inequality is inevitable nor implies that it is desirable. Growth is simply the size of the pie increasing. In principle, a bigger pie makes it feasible to give everyone a piece of at least the same size as before, and possibly more. This is the essence of the so-called Pareto criterion invoked by economists. But markets do not guarantee that as the pie grows, all its slices will increase – some can get smaller. Policy is needed to encourage inclusive growth.

Why should we care about equal distribution of the pie? I have three responses.

First, people care about “fairness”. Large inequalities in income or wealth are often viewed as unfair. To be clear, I am not advocating complete equality where everyone receives exactly the same piece of the pie independent of competence, effort and the demands of the market. This would create the classic moral hazard problem economists worry about. But the vast inequalities observed today are hard to justify based on these factors alone. Conversely, there is little evidence that a more equal distribution of income or wealth by itself reduces incentives to work and contribute to society.

Second, even if one does not care about inequality at all, in practice large inequalities create social unrest. We do not need to go as far as invoking the French or October revolutions. In recent years, sound economic policies that produced large aggregate gains have also generated considerable backlash where they generated winners and uncompensated losers. And this backlash can impede further growth when those left behind block further change. Trade reforms and the hyper-globalization of the past three decades are prime examples. The backlash against globalization we currently experience in many advanced economies shows not only that inequality matters to people, but also that the perception of being left behind interferes with policies that would promote growth.

Lastly, big inequalities in income and wealth often translate in inequalities in opportunity. There is evidence that rising income and wealth inequality in many advanced economies is driving disparities in health and education (which is why the Deaton Review is devoting particular attention to these aspects of inequality). People who emailed have asked me why focus on inequality in a developing country where 70% of the population live on less than $1.90 per day? But a country will not grow rapidly unless it utilizes its productive potential. Stunting, poor health, and inadequate education among the poorest segments of a society mean that people will be unable to realize their potential and contribute to the economy. Countries where women have limited rights and cannot contribute to the economy on equal terms not only miss the opportunity to draw on the labor and talent of half of their population, but also tend to face demographic challenges due to high birth rates. This points to the importance of a different dimension of inequality, gender inequality, and may serve a reminder that inequality goes beyond disparities in income and wealth.

So, “inclusive growth” is not an oxymoron. Rather, inclusiveness may be the only way to achieve growth today, in developed and developing economies alike.