So far, the blog has covered what corona can teach us about Africa’s global connections; the virus’ impact on society and academic life in Ghana; and the impact on democracy in South Africa. The latest post (below) discusses the situation in Cameroon, a country already affected by years of conflict.

With lockdowns as a result of the coronavirus descending across Africa, countries like Cameroon, which were already experiencing some form of conflict before the crisis, will take the hardest hit. Three years of separatist fighting have already left scars on Anglophones in the North-West and South-West regions of Cameroon.

The United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres, has appealed for a global ceasefire during the coronavirus pandemic. Some armed groups answered that call and are supporting a temporary ceasefire. For other groups, it is business as usual on the battlefield despite the looming threat of COVID-19. This mixed response is bad news for the hundreds of thousands of people forced from their homes during the three-year conflict. There is widespread concern about the devastating effect that the coronavirus in combination with the separatist conflict will have on the already struggling local economy and the jobs of millions of people. According to the World Health Organization, as of 9 April 2020, Cameroon was the third most affected country in Sub-Saharan Africa with 803 confirmed coronavirus cases.

The United Nations Secretary-General, António Guterres, has appealed for a global ceasefire during the coronavirus pandemic. Some armed groups answered that call and are supporting a temporary ceasefire. For other groups, it is business as usual on the battlefield despite the looming threat of COVID-19. This mixed response is bad news for the hundreds of thousands of people forced from their homes during the three-year conflict. There is widespread concern about the devastating effect that the coronavirus in combination with the separatist conflict will have on the already struggling local economy and the jobs of millions of people. According to the World Health Organization, as of 9 April 2020, Cameroon was the third most affected country in Sub-Saharan Africa with 803 confirmed coronavirus cases.

Lockdowns are not new in Anglophone Cameroon

In fact, separatists fighting for the independence of the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon have imposed lockdowns in the region for over three years now, with violence used to enforce the confinement measures. While the rest of the world is coming to terms with school closures as a result of the pandemic, children in Anglophone Cameroon have not been able to get an education for more than three years. This conflict, which escalated following the government’s heavy-handed response to peaceful demonstrations, has led to the loss of thousands of lives, a broken local economy, and run-down infrastructure. Thousands of people have fled the regions, some permanently, especially those who have the financial means to establish themselves elsewhere (often in neighbouring Nigeria or other regions of Cameroon). This, then, is the context that the coronavirus-driven lockdown is being introduced into.

Power struggles

The situation is exacerbated by a power struggle between the government and the opposition parties. Consequently, there is a lack of coordination in the fight against the pandemic. Professor Maurice Kamto, leader of the principal opposition party Mouvement pour la Renaissance du Cameroun (MRC) has criticized the government’s (lack of) response to the pandemic and has launched a fundraising initiative to counter the spread of the virus. This MRC initiative was opposed and outlawed by the Minister of Territorial Administration, Paul Atanga Nji, who published a press release on 7 April 2020 demanding the MRC stop the fundraising operations because they are organized ‘in defiance of the legislation in force’. The minister was supported by other opposition leaders, such as Joshua Osih of the Social Democratic Front (SDF) and veteran politician Bello Bouba Maigari, who accused the MRC of using the coronavirus crisis to score political points. The rap artist Valséro, released from prison last October as part of the presidential pardon that preceded a controversial national dialogue, and a known partisan of Professor Kamto’s MRC party, in response stated that, ‘People of Cameroon, by prohibiting you from organizing yourself in the fight against the spread of Coronavirus, the government has just made a clear choice. Between saving the lives of Cameroonians and retaining power, they chose to sacrifice you’ (on Cameroon-info.net).

Hunger and frustration

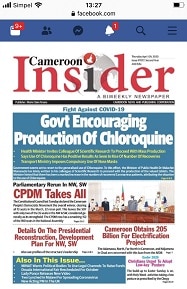

These squabbles have compounded the government’s chaotic response to the crisis. One newspaper has even reported that the government is encouraging Cameroonians to produce batches of chloroquine – the effectiveness of this drug in treating the coronavirus has divided global opinion. While this drama is unfolding, people continue to die in Cameroon’s rural Anglophone provinces, either as a direct result of COVID-19 or from the ongoing armed conflict, or from hunger as a result of the restrictions placed on communities in response to the coronavirus crisis. This is leading to a growing sense of frustration among the country’s citizens against all political players – the government, the opposition, and the armed separatists. The African proverb ‘when elephants fight it is the grass that suffers’ comes to mind. In this case, it is the impoverished citizens of Cameroon who are the grass.

Are lockdowns the right approach?

According to the United Nations, the coronavirus crisis will result in $220bn in lost income worldwide. Nearly half of all jobs in Africa could be wiped out during the coronavirus crisis, with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) reiterating the severe economic devastation for poor nations in Africa. The UNDP states that the coronavirus outbreak threatens to disproportionately devastate the economies of already impoverished countries as they gear up to tackle a health crisis with extremely limited resources. Given these dire warnings, one wonders whether depriving people of a source of livelihood (especially in conflict-ridden areas like Anglophone Cameroon) in attempts to contain the coronavirus will not lead to more harm than good. Only time will tell if we are doing the right thing by locking down entire economies, the mainstay for entire populations, in order to contain a virus that is unlikely to kill everyone. Self-isolation may not be a hardship for those who can afford it, but for millions of people across Africa who live a hand-to-mouth existence, staying home is not safe and could have dire consequences.

From Zimbabwe to Tunisia

Indeed, I have already started to see flaws in this strategy of asking economically vulnerable people to stay home in other parts of Africa. For instance, after imposing a nationwide lockdown about two weeks ago, Zimbabwe has recently eased some restrictions on movement and trade. For a country already confronting its worst economic crisis in nearly ten years, the coronavirus lockdown measures were ‘rubbing salt in the wound’ by threatening the livelihoods of ordinary Zimbabweans. And in a recent article by Sofia Barbarani on Aljazeera, it was reported that tensions are rising in Tunisia as people struggle to cope with hunger and unemployment amid the coronavirus outbreak. It is worth remembering that Tunisia is the birth place of the Arab Spring, which went on to have wider repercussions for an entire region; it may not be unexpected if the growing discontent about the lockdown in Tunisia also has wider implications. How long will people put up with being caged not only in Anglophone Cameroon but in all of Africa? Should Africa blindly copy pandemic containment measures from other continents? According to the words of Ivorian ‘coupé-décalé’ artists Siro et Luizo, ‘if malaria treatment leads to cancer, then malaria is better’ (song: ‘Mon pays est malade’, 2008. The cure should not be worse than the disease. In other words, lockdowns designed to contain the coronavirus should not end up taking more lives through poverty and hardship than COVID-19 itself.