Demographics are immensely important to economics. In fact, the relationship between the working-age population and dependents is so important that it explains between a third and half of economic growth. It is particularly important in low and lower-middle income countries where labour contributes the most to improvements in productivity.

And the higher the worker-to-dependent ratio, the faster the economic growth.

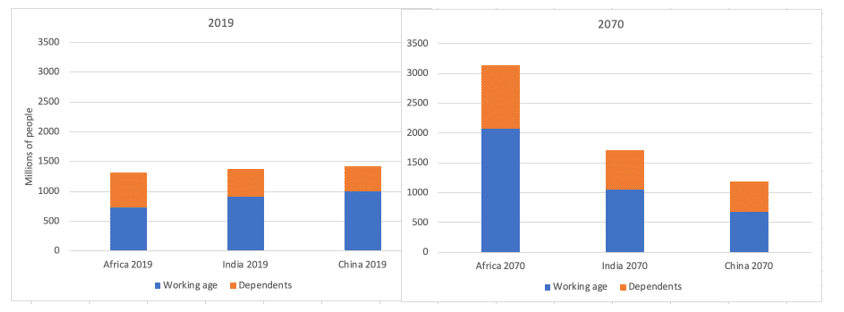

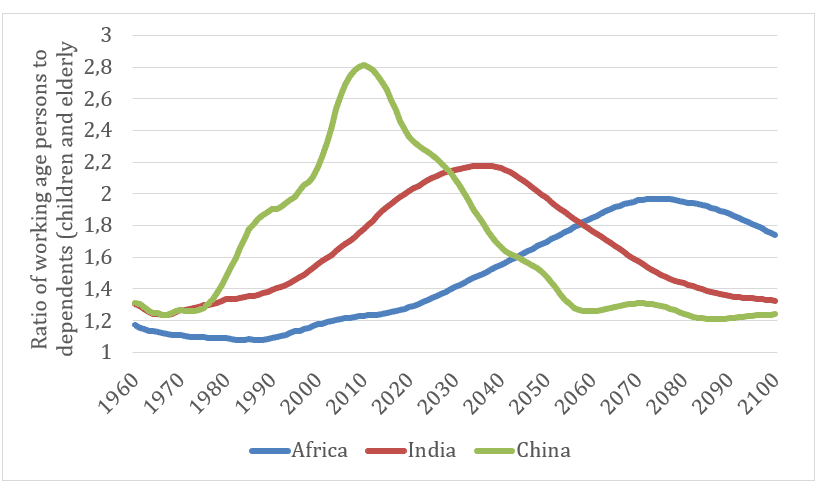

For Africa, demographics are particularly vital. When the working-age population (people between 15 and 64 years of age) is significantly larger than the dependent population (the very young and elderly), an economic window of opportunity known as the demographic dividend opens. However, contrary to the view of many policy pundits, Africa is several decades away from entering its demographic dividend. In part due to its one-child policy, China experienced particularly rapid economic growth up to 2011, when its demographic dividend peaked at an extraordinary high ratio of 2.8 persons of working age to every dependent. At that time, China had a population of roughly 1.4 billion people. Without a change in fertility rates, China’s economic growth is now set to decline quite rapidly as its working-age population has to support more dependents with each passing year.

Figure 1. Comparison of working-age to dependent population in Africa, India and China in 2019 and 2070 Source: International Futures v7.36, University of Denver

In the meantime, the worker-age to dependency ratio in India is improving and will likely peak at around 2036. At that point India is expected to have a population of around 1.6 billion people. Because the working-age to dependent ratio in India at its peak will be significantly lower than China, which was around 2.2, India will not be able to achieve the rates of economic growth previously attained by China, perhaps growing at around 6% per annum.

According to current forecasts, Africa only gets to its demographic dividend after 2054 and peaks much later, shortly after 2070, at a modest working-age to dependent ratio of 2.0. It is, therefore, unlikely that Africa will be able to achieve the rates of economic growth that China achieved in 2011, or the growth forecast for India mentioned earlier. By then, Africa’s population would have increased from its current 1.3 billion people to more than 3 billion people.

Using the International Futures Forecasting system from the University of Denver, I estimate that by 2072 Africa will only achieve an average economic growth rate of around 4% per annum, which is significantly below that required to provide employment and improve livelihoods for its large and expanding population. That is because Sub-Saharan Africa has a particularly young population with a large cohort of people below 15 years of age.

Figure 2. Ratio of working-age persons to dependents for China, India and Africa Source: International Futures v7.36, University of Denver

With few exceptions, average economic growth rates in Africa will be too slow and population growth rates too high to allow the continent to either rapidly reduce poverty or improve average incomes.

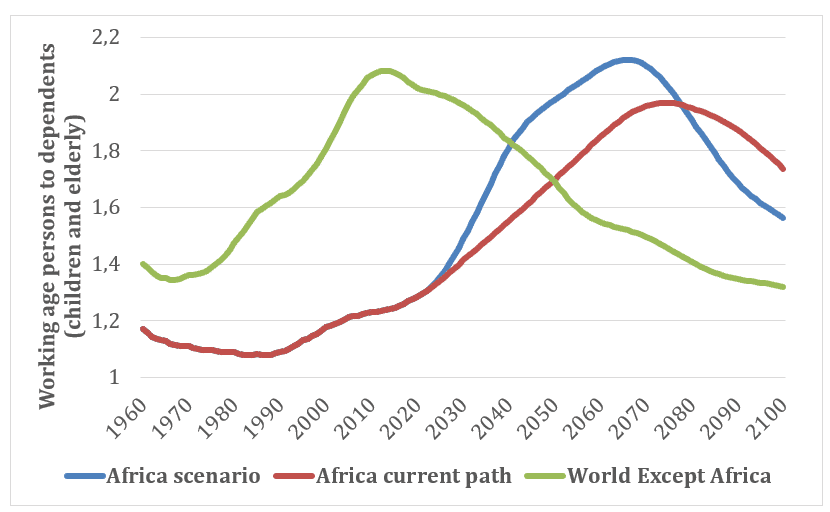

Interventions targeting family planning, clean water and improved sanitation, education, and women’s power, status and education can change this. A recent report on demographics from the Institute for Security Studies simulates a scenario that advances Africa’s demographic dividend by empowering women and meeting the pent-up demand for contraceptives use, which the UN estimates as equivalent to two less children per women. In that scenario, the continent will, by 2063 (the final year of the African Union’s Agenda 2063), have 400 million fewer people. Poverty will largely be eliminated and Africa will have an economy that is roughly a trillion dollars larger than would otherwise be the case. The result is that average incomes in Africa would be significantly higher.

The impact of that scenario on the ratio of working-age persons to dependents is depicted in Figure 3, which also compares the current demographic path for Africa to the end of the century with the working-age to dependent scenario in the rest of the world.

Figure 3. Ratio of working-age persons to dependents in Africa vs the rest of the world Source: International Futures v7.36, University of Denver

Africans need to engage candidly and robustly in public discussions and scholarly analysis of the economic and development implications of the continent’s large youthful population. Political leadership in discussing gender inequality and family size is vital, as are public media campaigns that demonstrate the health and economic benefits of smaller families.

In addition to investing in the education of women and girls, African governments in low- and lower-middle income countries should prioritize the accelerated roll-out of modern contraception. Such a programme should first meet the pent-up demand for contraception and then aim to significantly expand contraception use beyond current planning. This would advance the onset and intensity of Africa’s demographic dividend with substantive development benefits, including much more rapid economic growth and higher incomes.