Two INCLUDE research projects focus on non-state actors (NSAs) to explain the shrinking space for civil society organizations (CSOs) in some countries. These actors, such as businesses, ‘independent’ media and traditional authorities, clot with formal state institutions to intimidate and prevent CSOs from advocating for inclusive development. Acknowledging the plurality of repressive forces is important in two ways: 1) it shows that we have to look beyond the formal institutions of the state to identify the various, and fluid, forms of repression, and 2) it recognizes the need for an even more flexible and tailor-made approach to support CSOs operating within such contexts.

In 2017, INCLUDE, NWO-WOTRO and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) kicked off the research programme ‘New roles of CSOs for inclusive development’ to scrutinize the assumptions underlying the MFA’s policies to support CSOs. Part of the dismantling of these assumptions is to look at how CSOs can be supported within the context of shrinking civic space. Often, this context is explained as states reducing the operating space for CSOs through laws and in practice, ranging from limiting foreign funding to outright violence.

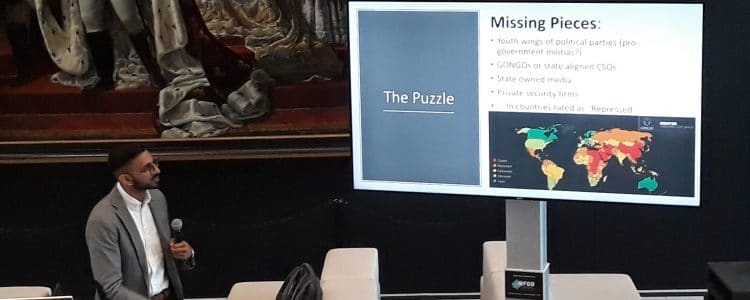

The importance of laws to protect the operating space of CSOs cannot be overestimated, as is argued by Dina Townsend (Tilburg University) in relation to Ethiopia’s new civil society law. However, on 25 June 2019, in a seminar organized at the MFA, researchers Luc Fransen (University of Amsterdam) and Dominic Perera (CIVICUS) pointed out that there are other actors than state actors to look out for when protecting civic space. Sharing his team’s interim findings on NSAs in Palestine, Bangladesh and Zimbabwe, Perera expressed deep concern about the alignment of states with unusual suspects, such as youth wings of political parties, government-oriented NGOs, state-owned media and private security companies. Fransen’s team added to this list by investigating the roles of businesses, religious groups and ‘independent’ media. According to Fransen and Perera, a major driver of their research was the lack of a systematic view on how these NSAs operate to limit civic space.

METHODS

Extending the imposition of restrictions on CSOs is described by Perera as “clean hands, but dirty gloves”. States ‘outsource’ the task of restricting civil society to parties such as those mentioned above. The methods that NSAs use vary, according to national and sub-national contexts, but also depend on the type of actor involved. Some methods limit CSOS at the level of the organization, while others are geared directly towards individuals within, or affiliated with, the organization. Roughly, three ways of limited CSOs can be identified:

- Damaging the reputations of CSOs by making accusations of terrorism, resulting in a decrease in funding by international donors, international travel bans and sometimes even violence

- Influencing public opinion through partisan media, war veterans and youth wings of political parties; this can lead to the disruption of meetings, attacks on activists and even torture, disappearance and murder, the threat of which can affect the mental health of activist and CSO staff

- The organization of business-friendly (or state-friendly) NGOs countering the narratives of critical CSOs

Some of these strategies target CSOs directly, while others are used to turn public opinion against them. Perera indicated that resistance by CSOs can increase public support for their work and become a ‘badge of honour’. The extent to which this takes place also depends heavily on public opinion towards states, businesses and other NSAs.

RESPONDING STRATEGICALLY: ADJUST, RESIST OR DISBAND?

The most strategic response to the threats imposed by NSAs depends heavily on the context within which the CSO operates, including the extent of support for CSOs by the public, by other CSOs and by international donors.

Looking at the role of public support, Perera finds very limited support for the tactic of ‘naming and shaming’. Respondents to the research argue that this is futile and possibly dangerous. He opts for a different strategy: to ‘resolve’ the issue through the more direct representation of constituents. The potential of this strategy is one of the focuses of his research, which now enters its final phase.

Fransen categorizes the responses by CSOs into three categories: they can either adjust, resist or disband. Some organizations have disappeared as a result of increasing pressure, while others have chosen to find a balanced mix between adjustment and resistance. Some organizations, for instance, have decided to drop advocacy activities, and focus on service delivery, as such activities are welcomed by the state and less likely to invoke repression.

Perhaps most interesting are the CSOs that are able to continue advocacy by manoeuvring strategically within the little room there is left. Fransen outlined a list of tactics that CSOs employ. Yet, given the sensitivity of the matter, this list cannot be shared here.

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR DONOR SUPPORT?

International donors already have enough of a diplomatic challenge to push states towards more supportive civil society laws (and practices). The issues mentioned above place an additional burden on donors that support CSOs. Hence, the question is: what can donors, Northern NGOs and other partners such as Dutch businesses and citizens do to address the situation?

- First, the survivalist tactics by CSOs to adjust and resist require the support of international donors and partners. This means flexible assistance beyond financial support. In additional, legal assistance, mental health support and practical training are of equal importance.

- Second, political bodies are advised to acknowledge the issue of non-state repression and influence policies. This applies to all levels, ranging from Dutch embassies to the European Commission.

- Third, Fransen argues to broaden the scope in assessing corporate responsibility; within firms supplying to Dutch businesses, we need to look beyond their circumstances in terms of social, human and environmental rights only and assess what partnerships they are part of, and if they are possibly involved in business with actors involved in repression.

- Finally, human rights ambassador Mariette Schuurman (discussant in this seminar, together with Dina Townsend) encouraged us to look at what consumers can do in terms of consuming products developed within these contexts. Given that civil societies can look good on paper, but can be ‘proxies’ of repressive states, she argued that different routes may need to be considered to empower CSOs for inclusive development.

This seminar was attended by an overwhelming number of interested parties, with over 100 representatives from the MFA, civil society and research. This widespread concern could be a first step towards a broader strategy for supporting CSOs under pressure.