The research programme ‘New roles of CSOs for inclusive development’ investigates the assumptions, solutions and problems underlying the civil society policy framework ‘Dialogue & Dissent’ of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Currently, all the research groups are conducting the empirical part of their research. The ‘Assumptions blog’ provides insight into the fieldwork of the research groups – the researchers share their on-the-ground experiences through this blog. This time, Dr Maaike Matelski and Selma Zijlstra (MSc) from Radboud University, from the research group ‘Civil society engagement with land rights advocacy in Kenya: what roles to play?’, share their field observations from Kenya.

Kenya is abundant in natural resources: it has fertile land, wildlife parks and coastal tourism opportunities. Since colonialism, national and international entities have been investing in land, often at the expense of local communities. Nowadays, mining opportunities are increasingly being explored. However, the issue of land has been central to Kenya’s conflicts and historical injustices and land grab cases abound.

Kenya’s political system has undergone significant changes since its new constitution came into force in 2010. While the constitution includes progressive provisions on land rights and civic participation, civil society organizations (CSOs) have been the main actors pushing for implementation and informing marginalized rural communities about these new rights. In this process, they also serve as amplifiers for local voices to be heard by the government. Without their efforts, the newly-established rights framework would likely remain a paper reality.

In our research, we look at the perceived legitimacy of various CSO actors working on land rights in rural areas. Through participant observation and interviews, we examine how professional civil society actors apply abstract knowledge on human rights to the everyday concerns of people who are often preoccupied with daily survival. How, and on what basis, do they claim to speak for these communities whose lives may differ significantly from their own?

In Mui, Kitui County, a large coal basin was opened up for tender in 2010, resulting in great interest from investors, as well as activists wanting to prepare the inhabitants for the consequences of mining. CSOs are concerned that the open-pit mine could result in the displacement of up to 20,000 people, as well as environmental degradation in the wider area. Local politicians have repeatedly visited the area to announce that coal would be mined soon. Yet the population has remained in the dark regarding the timeframe and the plans for compensation and relocation, which the national government is supposed to oversee.

As part of our research, we joined a local human rights organization, which has been providing governance training and legal assistance to the local community for many years. When the issue of coal mining emerged, they were among the first to inform the community about their right to information and the importance of free and prior informed consent. They also emphasized the inhabitants’ right to withhold consent and oppose the mine if the investors and the government do not fulfill their legal responsibilities. Other CSOs, including a regional faith-based organization, have come with a similar message, but have put more emphasis on the right to fair compensation and relocation. Meanwhile, various Nairobi-based organizations have responded to developments in the Mui area with activities such as land demarcation. Environmental activists have linked the local inhabitants to a broader anti-coal movement and organized a demonstration in Nairobi, in which people from Mui participated.

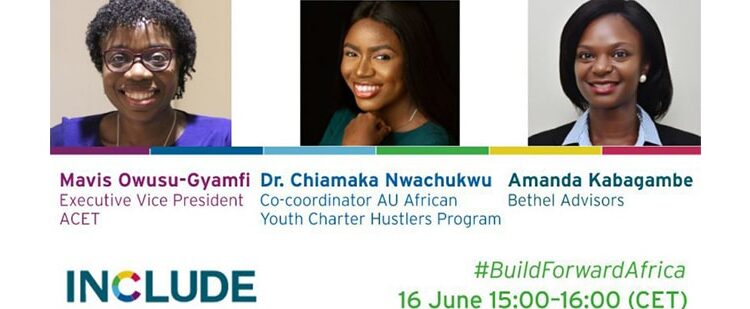

Anti-coal demonstration organized by CSOs on World Environment Day, 5 June 2018 in Nairobi. ‘Coal ni sumu’ means ‘coal is poisonous’ in Swahili.

So what positions these various organizations to operate in the Mui area? For the local human rights organization, it is its long-term presence, legal knowledge and political network that it derives legitimacy from. The ethnic and linguistic composition of its staff members also makes it easy for them to operate in the area, and helps them to amplify the voices and wishes of the Mui people. Some CSOs from outside the area have reportedly been rejected by local people, who became suspicious of outsiders after Kenyans from elsewhere started buying land speculatively in anticipation of compensation for land that might be used for the coal mine. The Nairobi-based environmental activists visit the area only sporadically, but offer access to transnational networks that can amplify the community’s resistance to coal mining. In this amplification process, however, some local nuances may be lost, such as the livelihood concerns of the population in what is one of the poorest areas of the country. The environmental movement presents green alternatives, but does not offer tangible options for people who may be tempted to sell their land.

In coastal Kilifi County, salt mines have been active since the mid-1970s. Over the years, many people have been evicted from their land with little or no compensation. Inhabitants of the area complain about the salting of wells, destruction of mangroves and fishing habitats, pollution due to brine water, dry soil and health problems. After the end of the Moi dictatorship, the farmers formed nine regional farmers groups. From these farmers groups, a local human rights organization was formed to act as a focal point. It subsequently became the most active organization in the area and is viewed by outsiders as the main representative of local people. It trains human rights defenders, raises awareness in the community, mobilizes media, instigates court cases, lobbies government agencies, conducts research, and tries to persuade companies to engage in corporate social responsibility activities. The organization relies on a human rights discourse and a narrative of negative corporate impact to justify its activities; stressing, for example, that people have been forcefully evicted from their ancestral land.

Like in Mui, the organization draws its legitimacy from its long-time involvement with local communities, as well as from its origin in local grassroots activism. Advocacy actions, such as media mobilization or lobbying, are reported back to the communities. The communities they work with rely on the staff’s expertise to choose the right strategy; therefore, communities do not always fully join in decision making, as they regard themselves not educated enough to know which actions to pursue. Challenges to the organization’s legitimacy include local people’s fatigue with the protracted struggle, as well attempts by corporations to delegitimize the organization and win over individual community members with benefits such as employment and scholarships, which the organization regards as a ‘divide-and-rule’ strategy.

As these examples demonstrate, how CSOs position and legitimize themselves in the field depends on the actors involved and the interests they prioritize. The CSOs portrayed here derive legitimacy from their expertise and knowledge on human rights, as well as their strong grassroots base and close relations with the affected communities. While the coal mining situation in Mui is still unfolding, the long-standing engagement by the organization in Kilifi shows that challenges such as community fatigue may complicate advocacy work. In Kilifi, the mining companies’ activities pose a challenge to the organization’s attempts to unify communities, while in Mui corporate actors have so far been absent from the field and the debate on advocacy strategies takes place primarily among the various CSOs in the region. These preliminary data confirm our assumption that the legitimacy of Kenyan CSOs engaging in land rights advocacy is time, situation and stakeholder dependent.