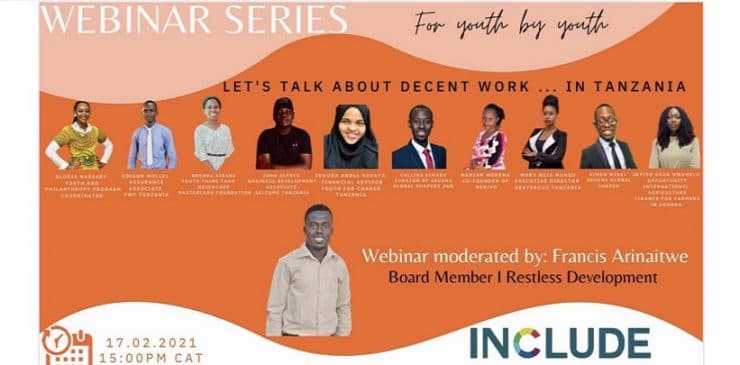

On the 17th of February, youth in Tanzania engaged with our discussion on ‘what and when is a job decent’, and delivered a contrasting interpretation to what has been previously covered in our webinar series. Participants defined a decent job as one that provides a fair income, social protection, and personal and professional development. They also stressed the importance of a job that is fulfilling and consistent with their values and beliefs. Like the Kenyan participants, youth from Tanzania outlined the difficulty of manifesting the reality of a decent job, in this case owing to the overrepresentation of youth in the agriculture sector (which is often characterised by insufficient income and lack of social protection) and the fact that young people are deprived of the appropriate channels and connections that will land them a decent job. The participants recognised the huge discrepancy between the formal and informal sector in Tanzania, and identified persisting gender inequalities, particularly when it comes to generating income, accessing productive resources and employment opportunities. In light of this, the following solutions were suggested to address the lack of decent jobs in Tanzania: Inter-generational discussions and mentorship; decolonising the way youth perceive the informal sector; and promoting gender equality as a cross cutting priority in policies, employment programmes and strategies.

The webinar was centred around the following questions:

1. Is a decent job only possible in the formal sector?

It is an undeniable fact that the informal sector is the main engine for job creation and economic growth in Tanzania. It is this sector that accommodates most of the youth in Tanzania. Despite

its merits, the informal sector suffers from a number of constraints including a lack of structure, use of rudimentary or low-technology tools, lack of social protection and low labour productivity. Whilst a lot of youth reap the benefits of this sector and thrive, many struggle to find decency in their informal jobs. As the participants delved deeper into this topic, they explored the extent to which there is a need to reevaluate the way we view decency. They highlighted the danger of looking at the definition of a decent job with a formal lens and how this may exclude the informal sector. For example, it is fairly simple to observe decency in the formal sector as it is more regulated, hence exaggerating the decent job narrative in this sector. They also recognised that formal regulations may not be applicable to this sector since there is not a one-size-fits-all-approach. Therefore, there is a need to devise a system that takes into account all the specific aspects of the informal sector and fill in the missing gaps.

2. Is ‘decent job’ different for men and women

The participants emphasised the significant gender lags in both income and economic participation: young women in Tanzania are placed in low-skilled, low-wage and hostile jobs. Agriculture accounts for the highest share of employment in Tanzania, especially amongst youth, however, a large proportion of the workers in this sector are women, who often act as unpaid helpers. The majority of rural women in Tanzania are subsistence farmers who face poverty due to the seasonal nature of agricultural work, and a significant number of young females from rural areas have additional occupations which tend to be unpaid. Because of their limited access and control over resources, young women from rural areas find it difficult to translate their labour into earnings that could ultimately lift them out of poverty. Similar to our previous webinars, the participants pointed out that the lack of education amongst young women widens the existing gender gap within the workforce. Efforts are needed to promote gender equality in labour markets and to support education as well as decent job initiatives in rural areas.

3. How has COVID-19 affected the narrative of decent jobs?

Like the rest of the world, Tanzania’s labour laws and job market neither envisaged nor prepared for the COVID-19 pandemic. As demonstrated in our previous webinars, the effects of COVID-19 were deep and disproportionate in the informal sector. As a result, the significant number of youth concentrated in this sector bore the brunt of this pandemic. The formal sector was also not immune to the effects of the pandemic, as many workers in this sector experienced a huge drop in hours and wages. The Tanzanian webinar brought a different angle to the discussion on youth employment and COVID, as they observed the different impacts of the pandemic along gender lines. The weaker position of women in the labour market has been exaggerated during the pandemic, with women becoming even more vulnerable to lay-offs and precarious working conditions. Moreover, women have been forced to take on more responsibilities in the household, and gender-based violence has intensified during the pandemic, thus adding to women’s vulnerable state and cacacity to work. In view of this, it is pivotal to recognise the gendered dimensions of COVID-19 and analyse what can be done to prevent widening inequalities.