On Tuesday, 17 November 2020, INCLUDE hosted a two-hour virtual session on productive employment based on the experiences and evidence from the African Policy Dialogues (APDs). The session brought together over 50 delegates including Platform members, policymakers from the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, partners implementing APDs in Africa, and guests from organizations involved in evidence-based policy processes. The session consisted of two panel presentations followed by floor discussions. The first panel discussed evidence from the APDs and the second was on lessons from engagement with policymakers. The key messages from the session are as follows.

Employment remains a priority agenda and APDs play an important role

Creating decent jobs remains a key challenge in Africa. Although unemployment is relatively low (6.8% on average in 2018), most of the available jobs do not offer fair remuneration, stability or decent working conditions. Some middle-income countries, such as South Africa and those in North Africa, have had success with labour market policies. The question is how to generate evidence about these successes and share it with diverse and relevant policy actors in Africa. To address this, APDs link policymakers with research, by generating evidence about good employment policies and sharing it with policymakers and implementers in Africa and the Netherlands. The role played by APDs varies depending on the country, as do their outcomes.

Evidence from APDs on employment creation

In Ghana, political parties have recognized youth employment as a priority agenda, and the party that won the election in 2016 actually titled its manifesto ‘Agenda for Jobs’. This agenda struck a chord with the public, propelling them to victory. The new government initiated several employment creation interventions, such as the ‘One District, One Factory’ initiative and the Nation Builders Corps (NABCO), which provides employment for post-secondary school graduates.

According to utafiti sera (research policy) APDs in Kenya, Rwanda and Nigeria, the key to employment creation is: the transformation of agriculture through the use of modern technology in production and marketing; enhancing equality in access to land, markets, credit and skills to address gender disparities between young women and men; strengthening youth organizations and groups in agriculture; creating youth mentorship platforms; and shielding actors from political interference, especially in the sugar and cotton value chains in Kenya and Nigeria.

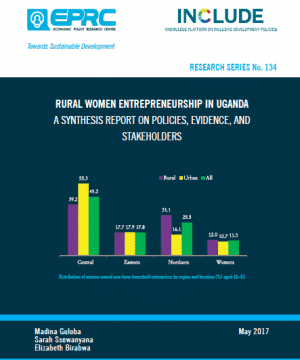

In Uganda, it is important to acknowledge that the needs of women entrepreneurs vary, and this should be considered in programmes and policies aiming to address their needs. Women entrepreneurs differ in terms of their location (urban, peri-urban, rural), education level, assets owned, income earnt, business knowledge, risk profile and management ability. For example, women entrepreneurs who are more educated generally prefer to work independently, rather than through associations. Furthermore, most women entrepreneurs in rural areas are prone to deception by other traders and tend to access credit from their associations, which survive through solidarity and kinship ties.

In Mozambique, one of the approaches used to address unemployment is inclusive governance, which is more than just involvement in decision making, but includes empowering youth to participate in decision-making processes. This can be achieved by enhancing the capacity of youth to participate in governance to transform agricultural production and food security.

Although agriculture and the informal sector provide most of the jobs in Africa, the extractive industry dominates exports. However, the extractive sector does not provide many jobs. To address this, Morocco has created a state fund from the extractive sector to invest in employment creation in other sectors. Unfortunately, this is not the case in other countries, like Mozambique.

Changing role of governments in employment creation for the youth

In the past, many governments in Africa saw their role as that of creating an enabling environment for job creation by the private sector; however, this appears to be changing. Many governments are currently investing directly in job creation or partnering with the private sector to do so. In Ghana, for example, the government has invested in manufacturing (‘One District, One Factory’) to increase the demand for labour and has established the NABCO to create jobs for unemployed post-secondary school graduates. In Mozambique, the government has created a Secretariat for Employment of Youth at the Office of the President. Furthermore, to address the mismatch between education and the labour market skills required, the governments of Ghana, Uganda and Mozambique have invested in technical and vocational education training (TVET). For example, in Uganda, the Youth Livelihood Programme was established to provide funds for youth-initiated projects. One of the challenges is that the coordination between youth employment creation programmes is lacking or weak.

Lessons learnt from engagement processes with stakeholders

The following are the main lessons that can be drawn from the APDs:

- Generating research on issues like employment creation can appeal to political parties: In Ghana, the opposition political parties have embraced the employment creation agenda. This strategy was successful in appealing to voters, as the main opposition party won the election in 2016 on the back of this agenda and has just been re-elected (in December 2020). This government has shown its commitment to addressing the challenges of youth unemployment.

- Research uptake takes patience and perseverance: Research uptake and shaping policies can be a slow process, because there are so many stakeholders with varied interests – so it is a balancing act and takes time.

- Trust between stakeholders is important: Based on the work of the APDs in Kenya, Ghana, Nigeria and Rwanda, trust between stakeholders is important for engagement and research uptake.

- Political cultures and contexts differ: Political cultures and contexts differ and influence engagement strategies and policymakers’ willingness to consider evidence. For example, in Rwanda, government officials are keen on the evidence about what works and actively participated in engagement. In Kenya, the policy space has multiple actors with divergent interests, which makes it difficult to identify who to target. In Nigeria, evidence about the disparities in wages between men and women who work in the rice processing industry was presented to stakeholders, including senators, who appeared enthusiastic about it, but follow up steps for action were not successful. In Uganda, engagement processes that are based on the needs and interests of stakeholders and are communicated in a language that they identify with are, therefore, more likely to succeed.

- Strengthen the capacity of stakeholders in the research-policy space: The capacity of stakeholders to synthesize and package evidence in forms usable by policymakers is weak and should be enhanced.