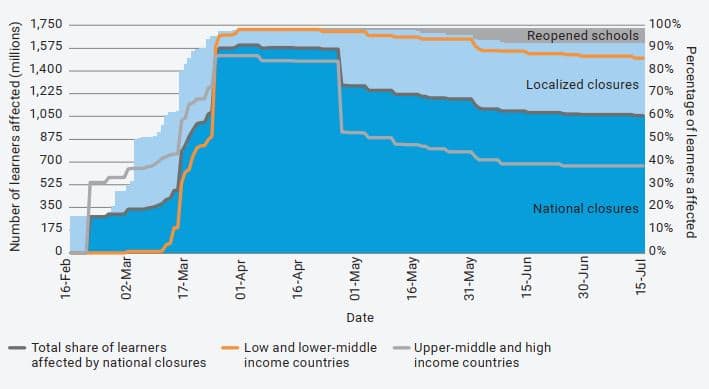

COVID-19 has caused the largest disruption to education systems in history. Closures of schools and other learning spaces have impacted almost 1.6 billion learners in over 190 countries, representing 94 percent of the world’s student population. As of mid-July 2020, over 1 billion learners worldwide were still affected by national closures, and this was proportionally much greater in low- and lower-middle income countries (80-85% of learners) than in upper-middle and high-income countries (35-40%) (Figure 1). In Africa, the pandemic has been superimposed on an existing learning crisis and growing inequalities in capabilities. The sudden increase in demand for remote learning has made the divides in digital infrastructure, teaching capacity and both basic and advanced skills clear and unavoidable. Despite numerous efforts to continue funding and delivering education remotely, gaps in access and quality have widened over the past 7 months. These trends threaten to reverse the progress made in education over the past two decades, and pose great risks to meeting the learning potential of current and future generations. More optimistically, if funded and managed well, new and pre-existing innovations have the potential to close divides and restore long-term human development.

Figure 1. Number of children affected by school closures globally, by development group (source: UNESCO, 2020)

1. Responses to COVID-19 in the field of education

- Initial education responses in March were strict and uniform, driven solely by the need to avoid a health pandemic. A range of strategies have now developed across Africa, reflecting diverse risks and capacities in multiple areas. Schools in some countries (Ethiopia, Mozambique) remain closed, while others (all North African states, plus Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Uganda, South Sudan and Zimbabwe) are partially open, and a third group (most Western African states, plus Tanzania, Namibia, Botswana, Zambia and Congo) are fully open. These decisions have depended on health and safety factors (adequate sanitation facilities in schools; the local spread of COVID-19), educational and socioeconomic factors (the ability to provide and access remote learning tools and content; the dependency on school meals for child nutrition), and the level of decentralisation of education governance within each country.

- A key report by the Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA) maps the COVID-19 emergency education strategies of 13 African countries. It includes a list of major learning platforms and portals, and initiatives for inclusive education (from sign language to zero-rated content to non-formal education). The report highlights that ICT, finance and teaching capacity are the major gaps to recovering and furthering African education systems. According to ADEA, best practices observed during the crisis have included optimising the use of existing channels (e.g. radio and TV), using diverse tools, establishing state-led multi-stakeholder education committees at national and sub-national levels, creating systems for validating educational content, and partnering with private and media organisations.

- A burst of new activity, led by a range of public and private actors, has emerged around digital innovation and emergency education, with a lot of international support in this field. Initiatives like AfricaConnect3, funded by the EU, have tried to enhance online learning through discounted data bundles and zero ratings for educational websites. The UNESCO COVID-19 Education Coalition has one of its three pillars dedicated to connectivity and focuses on partnerships between large technological companies and African states to overcome the insufficient knowledge infrastructure. It is important not to forget existing and tested innovations in IT for learning, but to scale up in a coordinated way that maintains local ownership and reconsiders inclusive principles in the process.

2. Impacts on different vulnerable groups

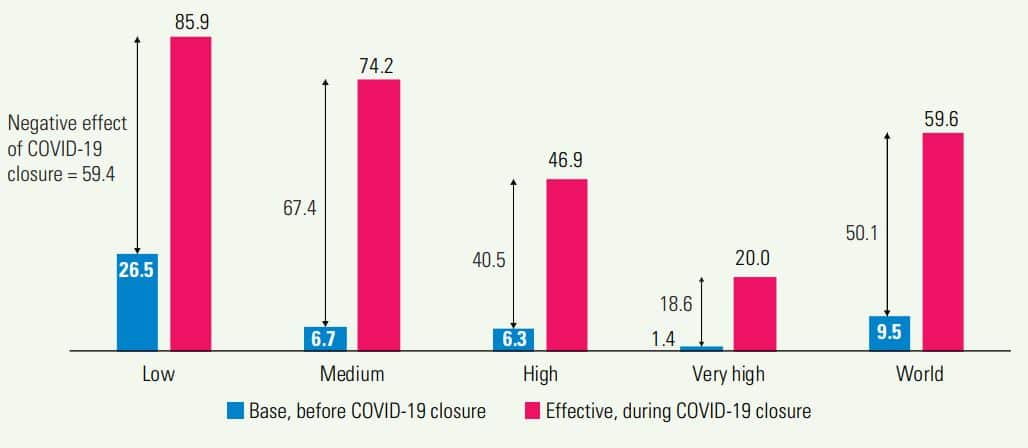

Despite the ramp up in the use of digital tools for learning, the effective out-of-school rate (the proportion of learners without opportunities to continue structured learning) in low human development countries was 86 percent in June, 4 months after the crisis began – levels not seen since 1985, and more than 4 times higher than very high human development countries (Figure 2). This is due to a stark digital divide as well as sociocultural factors which prevent the majority of learners in developing countries from accessing opportunities to learn outside the classroom, even when they exist.

Figure 2. Short-term effective out-of-school rate for primary education, Q2 2020, based on data for 86 percent of primary-aged children worldwide (source: UNDP, 2020)

- Although reported cases of the virus have been concentrated mostly in urban areas, rural areas have suffered immensely in terms of education due to poor connectivity. In sub-Saharan Africa, 89% of learners do not have access to household computers and 82% lack internet access. Furthermore, while mobile phones can enable affordable access to information and connection with teachers and other students, over 26 million learners live in locations without mobile network service. Even in African states that have used widely accessible technologies such as radio and television to keep students learning, the digital divide reveals the limits of Africa’s remote areas to benefit from digital education.

- The impacts on education in Africa have varied not only geographically, but also between socioeconomic groups. The extreme poor, girls, refugees and students with disabilities, many of whom were already behind in their education, have suffered the greatest disruptions to learning during the crisis. Since this time last year, teenage pregnancies have doubled in Uganda and tripled in Kenya, child marriage has doubled in Malawi, and violence against girls has spiked in many countries, heightening their risk of dropping out. 600,000 refugee children have been out-of-school in Uganda since the end of March, amounting to significant losses in learning and development. UNESCO estimates that around 10 million children may never return to school due to rising child poverty.

- Different levels of education have experienced their unique struggles, but many similar challenges are being faced across the education system. Remote learning has proven to be a poor substitute for face-to-face teaching of practical and technical courses in TVET Early childhood and primary schools are the least likely to have sufficient access to the necessary technologies needed for distance learning. And higher education institutes have struggled to maintain the quality of learning content in the transition to online teaching. At the same time, the digital competencies of staff and students to navigate and use new tools for learning, and the affordability, reliability and speed of internet, have been problematic across the board. This insight can be used to develop better management and prioritise reforms.

3. Impacts on longer-term inclusive development

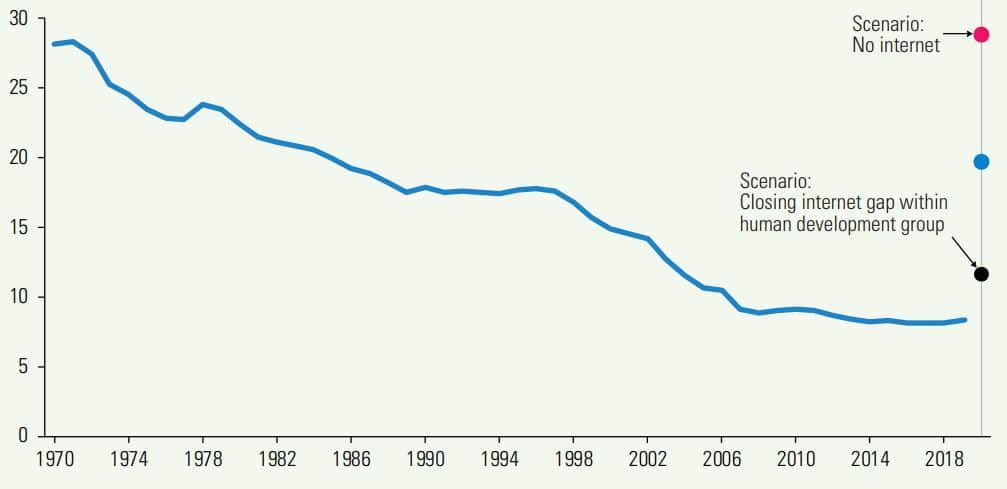

If the current setbacks in education continue, it is predicted to erase the past six years of progress in human development, and cost $10 trillion through lost learning. However, it is not all doom and gloom. If equality in school access is restored, education systems would bounce back. In a scenario with more equitable internet access – where each country closes the gap with the leaders in its human development category – the decline in human development would be more than halved. There are many building blocks in place to achieve this, but equally many challenges to overcome.

- Promisingly, closing the gap in internet access in low- and middle-income countries is affordable, costing $100 billion (about 1 percent of the fiscal programmes announced globally this year) according to estimates made in 2018. Unfortunately, COVID-19 measures could increase the annual financing gap to achieving SDG 4 by 2030 in LLMICs by up to one-third, and financing for education so far during the pandemic has been nowhere near sufficient and crowded out by other priorities such as emergency healthcare and income. The Global Partnership for Education unlocked $500 million to help developing countries mitigate the impacts of the pandemic, while Education Cannot Wait called on donors to raise capital, but has struggled to reach its target. Even with new innovative financing methods like the International Finance Facility for Education, there is a great need to decrease dependence on external funding and target spending on certain activities like connectivity and training. Taking preventative measures now would avoid curing the problem later at a much higher price.

Figure 3. Scenarios for the effective out-of-school rate for primary education, based on the equality of internet access (source: UNDP, 2020)

- Significant opportunities exist to change curricula, teaching methods and management of education activities in order to build relevant human capital and link better to the job markets of today and tomorrow but these changes need to be tailored to reach all groups of students. DRAWing away from the curriculum of the past argues that adding creativity and digital skills to the core STEM skills is critical to navigating economic and social trajectories. A survey by eLearning Africa and EdTech Hub found that educational TV and radio are seen as the most important technologies for sustaining learning at primary level, while at the secondary level, online learning is considered most important. In addition to relevant curricula and diverse modes of delivery, to be truly inclusive, learning must involve meaningful connectivity (affordable and regular internet, appropriate devices), and support and training for all teachers to ensure their readiness to engage in digital learning.

- Debates and initiatives to leverage ICT for education in Africa existed well before the onset of COVID-19, but the pandemic has created a new sense of urgency and fast-tracking towards digital modes of delivery which has not allowed for sufficient preparation, variation, or conversations around challenges and opportunities. Initial evidence shows that public education institutions across Africa are facing multiple challenges in the shift to online learning, highlighting the need to draw upon prior knowledge and experience, and focus on scaling up and coordinating tried and tested interventions to avoid falling into the same traps as before. Although crisis responses require a certain level of flexibility and letting go of past assumptions, they should not ignore or make redundant all prior debates and efforts, and ensure balance between action and reflection.