Since mid-March, countries around the world have imposed strict lockdowns to contain the spread of COVID-19, disrupting the livelihoods of billions of people around the world. The hardest hit have been those who were already poor or who fell into poverty since the pandemic—the “new poor.” In response, many countries launched unprecedented relief packages to cushion the economic and social impact of the pandemic. Social protection measures have grown exponentially: according to the most recent update of the World Bank’s database, since March a total of 200 countries/territories have planned or put in place over one thousand social protection measures, with social assistance accounting for more than 60 percent of them. New or scaled-up COVID-19 social assistance in the form of cash transfers now reaches nearly 1.1 billion beneficiaries, one in every six people in the world. Most of these were designed, financed, and implemented by developing country governments themselves. Especially with the constraints of COVID-19, digital technology has played a critical role.

In a new policy paper, CGD draws on early evidence from selected countries on the use of digital technology to implement these government-to-people (G2P) social transfer programs. Their review suggests that an important objective for policymakers in the post-COVID period will be to build on the capabilities developed during the crisis to strengthen social protection and payment systems and render them more inclusive, effective, and sustainable. This includes addressing the challenges faced especially by women, who are often digitally disadvantaged. Countries have an opportunity to lock in gains in the identification and coverage of beneficiaries, as well as financial inclusion, and to transition from one-off systems to help the “new poor” towards more permanent arrangements to strengthen the architecture of social protection systems in the future.

How countries use digital technology to scale up COVID assistance

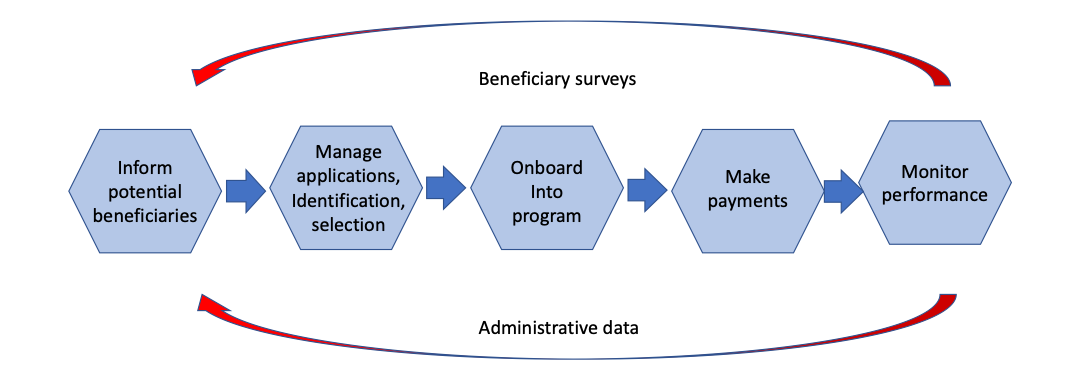

To run a social protection program, governments need to identify potential beneficiaries, communicate with them, and transfer funds. Digital ID systems, mobile communications, and digital payment systems therefore comprise three important building blocks for social protection programs. In addition, integration across social registers and other databases is important for a coordinated response: data integration is therefore a fourth critical dimension. Digital technologies play an important role throughout the entire “social assistance value chain” associated with G2P programs and payments: (i) informing potential beneficiaries about programs, (ii) onboarding them (in cases where they are not already included in existing programs), (iii) identifying them, (iv) screening them for eligibility, (v) making payments, and (vi) following up to resolve problems and grievances (see chart below).

Social Assistance Value Chain

Lessons for policymakers

Information is still limited on how well new or rapidly scaled-up social assistance programs have functioned; in particular, there is a dearth of demand-side survey evidence on the experience of beneficiaries receiving transfers and the likely magnitudes of inclusion and exclusion errors. Nevertheless, the emerging picture provides some indications of how investments in digital systems and their deployment along the social transfer value chain have been facilitating the response.

Investments in digital systems have played a critical role in scaling up programs and payments. Especially with constraints on in-person interactions due to the nature of the pandemic, many countries have followed a “digital first” approach to design and deliver social assistance. This has proved to be a lifeline for many during lockdowns and the disruption of entire economies and societies over the last several months. Digital systems have facilitated the processing and payment of COVID-19 assistance across many countries on a scale that would not have been remotely feasible without them. Countries with stronger digital infrastructure—including ID, mobile, and payment systems and digitized social registries—have generally been able to implement and disburse emergency assistance programs more rapidly than those without them.

In-person backup processes are essential. Innovative and flexible digital implementation can help to reduce the risk of digital exclusion. Nevertheless, even in countries that have made major digital investments, backups are essential, whether to reach populations with less digital access or capacity, adjudicate claims and grievances, or deliver emergency relief as a complement to digital payments. Local governments and nongovernmental organizations have sometimes played vital roles in helping vulnerable individuals and groups who fall between the cracks in mainline systems.

Digital campaigns can galvanize “active” beneficiaries. Multimedia campaigns inviting applications for support can mobilize people and generate awareness of relief programs. Many countries invited applications for emergency relief through mobiles, WhatsApp or websites. All received very large volumes of responses in a short period, sometimes overwhelming channels. Transferring funds to the accounts of existing beneficiaries saves these steps, but some beneficiaries may not be aware that they have received transfers, especially if their accounts have been dormant for some time.

Digital onboarding and screening can work—up to a point. Digital technologies have significantly facilitated remote onboarding of new beneficiaries. In addition to digital onboarding, the new emergency programs have relied on digital screening to handle their very large numbers of applications, often using multiple government databases linked by a unique and digitally verifiable ID number or—as in the case of Togo—the voter ID number. However, digital onboarding has limitations. A sizeable minority of people in developing countries lack access to, or control over, mobile phones or the capacity to use them to apply for or to receive grants. Gender inequities can sometimes be a particular concern for access; the urgency of COVID-19 responses can result in programs that fail to address the specific impacts of COVID-19 on women and girls. And digital screening against multiple data sources can result in exclusion errors and long delays in payment unless these sources are of high quality.

Digital payments systems have played a vital role despite some limitations. Countries have used a variety of approaches to deliver scaled-up payments to beneficiaries—financial accounts (banks and mobile money), as well as digital vouchers, e-wallets, and other mechanisms that do not offer a full range of financial services. Some have taken advantage of the crisis to expand financial access, including by using tiered know-your-customer to facilitate the remote opening of bank and mobile money accounts. A review of six countries with active onboarding programs found potentially 60 million new accounts were opened since the onset of COVID-19, which would be approximately 4 percent of the global unbanked population. In some cases, remote opening had been permitted for the first time. Such regulatory streamlining and innovation can be a positive legacy of the COVID-19 period.

Lower transaction charges spur digital payments but may not be sustainable after the COVID-19 emergency. Several countries have initiated emergency measures to encourage less use of physical cash during the pandemic. Our review suggests that incentives provided during the COVID-19 crisis can accelerate the transition from cash to digital payments, but it may be difficult to sustain such reductions in fees on a purely commercial basis over the longer run.

Communication is central, even when scaling up existing programs. Clear, simple, and timely communications are essential, especially for new cash transfer programs. Emerging evidence suggests that beneficiaries may not have known that they received them. By and large, scale-ups through existing systems have proceeded relatively smoothly. They can take advantage of established beneficiary lists, awareness among beneficiaries, and payment rails laid down over many years. Even then, examples show some of the difficulties that can accompany scaling up, in addition to the possibly limited capacity of the payments system.

Integration of beneficiary databases facilitates a coherent response—but raises concerns around data privacy. With highly integrated social benefit systems linkable to other government databases through the national ID, countries like Pakistan, Namibia, Turkey, and Brazil have been able to implement a coordinated response to reach a large number of people, screening for unique beneficiaries and to ensure that beneficiaries are not receiving support from multiple programs. From the short-run perspective, the ideal is a highly integrated national system with existing and new programs able to seamlessly onboard applicants for assistance and to allocate resources efficiently among them. However, this raises an inherent tension between administrative efficiency and safeguarding of personal information. The availability and access to personal data will only increase over time as citizens’ digital footprints expand, increasing the ability of governments to draw on a wide range of data about them—potentially even extending to real-time monitoring of activities such as mobile phone use patterns. It will be important to ensure that such emergency responses do not undermine measures to preserve data privacy in the longer run.

The COVID-19 period will undoubtedly spur further use of digital mechanisms to deliver social protection. Our review suggests that an important objective for policymakers in the post-COVID period will be to build on the capabilities developed during the crisis to strengthen sustainable social protection and payment systems that are both inclusive and effective, in particular addressing the challenges faced by women, who are often digitally disadvantaged. It also provides an opportunity for countries to lock in the gains in identification and coverage of beneficiaries, replacing one-off assistance to the “new poor” with something more continuous, permanent, and—ideally—universal. There is a need to rethink the social protection architecture altogether and lessons from the COVID response provides a good starting point.