When talking about the ‘middle class’, several questions emerge: Who exactly is middle class? And what is their position in society? When this has been established, then one can address the question about whether this group is a driver of inclusive development.

A first point, of course, is that Africa is a continent of more than 50 countries and it is far more heterogeneous than is often acknowledged. But many have a low median per capita income. In the Netherlands, this mean income is called the modaal inkomen and is more than US$ 100 a day (gross). The average income is around 80% of the median income. Using a recent World Bank definition for ‘middle class’ in Latin America (US$ 10-100), this would make the median household in the Netherlands middle class. In other words, a very large proportion of Dutch society belongs to the middle class.

However in most African countries, a person living on around the median income is still poor, often very poor. If we take for example Egypt, a recent newcomer to the group of (lower) middle income countries and certainly not the poorest on the African continent, we see that about 25% of the total population lives in poverty. An average household earns less than US$ 12 a day. For a family of six, which is not uncommon, this means less than US$ 2 per person per day, the international poverty line. Since Egypt is not a very unequal country (unlike an increasing number of African countries), the median is not too far off this US$ 2 per person per day. In fact, even the top 4% of Egyptian households spend just little over US$ 22 on average per day. In other words, the median household could be considered poor by international standards. Studies on mobility of not too long ago have, moreover, shown that many people hover around the poverty line, which suggests that even life above the poverty line is very uncertain and a constant struggle. One could wonder if these people are to be considered middle class and the drivers of inclusive development.

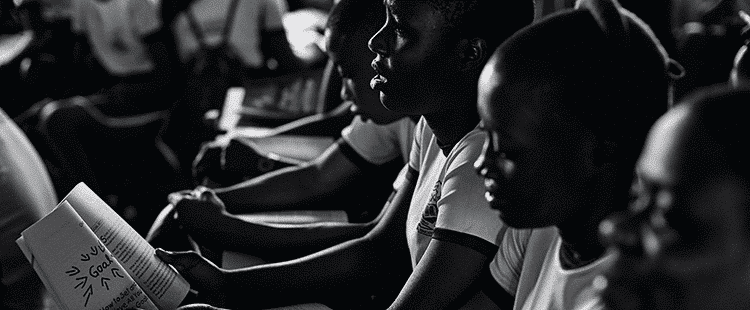

Nancy Birdsall, the president of the Centre for Global Development, calls the group of people that live a few dollars above the US$ 2 per day line ‘strugglers’ or ‘strivers’. At all times, this group remains vulnerable and runs a serious risk of falling back into poverty if anything adverse happens. Even if a head of household earns US$ 10 per day (which, with a monthly amount of US$ 200, is a professional’s salary in many countries), this still means a per capita income of no more than US$ 2 per day. This shows that even professionals like teachers, health workers and social workers in poor countries could be classified as strivers.

To ensure that the ‘middle class’ is a meaningful force in development, one therefore needs to think about policies that promote income stability and development. The middle class needs public policies that allow them to become more resilient, to absorb external shocks and to think of the future and not have to struggle and strive every day.

Inevitably, in my opinion, a conversation about instability leads us to a discussion on inequality. I agree with Nancy Birdsall who has said that, after the growth and pro-poor approaches dominated for some time, it is good to see that the notion of inequality is gaining ground. The difference between pro-poor and inequality is fundamental. One could make the comparison with what happened concerning women’s empowerment. Initially it was called Women in Development. And that is what it did: it tried to improve the situation of women. But the approach did not look at their position regarding others and simply tried to make their lives easier or better. By contrast, Gender in Development looks at the socially constructed power relations between men and women. And hence addresses the position of women, rather than only their situation. The same can be argued about the difference between pro-poor policies and policies that address inequality. Consequently, while pro-poor policies are only required to address the poor and improve their situation, policies that want to reduce inequality, or call it redistribution if you will, inevitably also need to work with interventions that affect the upper layer of society.

There are many ways to secure the stability of the middle class and strength their ability to be a driving force for development. Quality education, access to credit, decent job opportunities and a conducive environment for private entrepreneurship are examples often cited. Considering that Africa’s middle class is actually struggling to survive, social protection policies and programmes financed by taxes could also make a strong contribution. Here the World Bank’s point, which was made in its report on Latin America, also applies to Africa: ‘Central to the region’s prospects of continued progress will be its ability to harness the new middle class into a new, more inclusive social contract, where the better-off pay their fair share of taxes’. To make the middle class in Africa a driving force for development, an inclusive social contract is required where policies that address inequality and redistribution policies are key.