The implications of policy responses to COVID-19 for socioeconomic inequality

In this news-item, we identify the various national and local policy measures taken to suppress the COVID-19 pandemic and to support African economies, communities and workers. We ask what they mean for ongoing and planned development programmes and for the livelihoods of people in Africa. Our main focus is on if and how current policy trends and practices will affect socioeconomic inequalities (both between and within countries), and on what can be done to prevent this from occurring by supporting the poorest and most vulnerable.

To discuss how COVID-19 and national and local governments’ policy responses affect inequality and those that are most vulnerable, we structure our update according to:

1. Policy options and responses, including timing and implementation, with a focus on:

- The severity of lockdown and disease prevention measures

- Healthcare system management and capacity building

- Resource mobilisation and social protection

- Economic recovery and stimulation

2. The short-term impacts on vulnerable groups of these policy choices (including changes in employment and income opportunities, and access to services and social protection), in particular:

- Youth

- The extreme poor

- Fragile and marginalised communities

- Women

3. The longer term impacts on inclusive development, including:

- Access to social services and infrastructure (particularly healthcare, sanitation, education and social protection)

- Strength of governance (management, cooperation and emergency response planning)

- Structural transformation and employment (which sectors are growing/shrinking, how are policies facilitating/hindering this shift, and who is left behind)

28.04.2020

As coronavirus cases have risen throughout Sub-Saharan Africa in the past weeks (albeit slower than expected), and global economic disruptions have impacted many of the region’s industries, responses have been ramped up at all scales. Countries are in different phases of the crisis, with varying degrees of preparedness, prevention and protection. While certain countries (Ghana, South Africa, Zimbabwe) begin to relax lockdown measures to spare their economies, lockdowns are just starting or being extended in others. And while multiple governments have introduced or expanded social protection programs, in many cases it is boiling down to communities to fill gaps in critical services.

Community surveys are being used to gage the immediate effectiveness of COVID-19 interventions and understand the socioeconomic impacts of the crisis at local level. An interactive dashboard by Geopoll presents public opinions on the adequacy of actions by governments and businesses, including preventative measures (such as hygiene and distancing), testing and food provision, in 12 African countries. Responses have been met with mixed popularity and support, and the overall level of concern of African citizens is high around health, safety and recovery.

An extensive World Bank Group report analyses more formally the suitability and effectiveness of recent African and global policy choices, and discusses the varying welfare impacts under a range of scenarios. Among a list of options, the report prioritises healthcare and technical capacity given the fiscal and operational constraints of many African governments. Although consequences are being felt unevenly across countries, sectors and population groups, the region faces common challenges to food security and access to livelihoods, making coordination and cooperation (rather than autarky) critical.

Although the number of reports like this is increasing, there are more questions than answers at this point. A lot of sources reiterate the same over-generalised ideas and arguments, and governments are having to act before specific data is available. This makes data-oriented initiatives, like the one by IBP which monitors service provision in informal settlements in South Africa (particularly clean water, sanitation facilities and waste removal), vital for driving evidence-based responses.

This week, the news item is focused around the emerging evidence on COVID-19 and education in the African countries, including the main challenges and opportunities presented for inclusive development.

Social protection update:

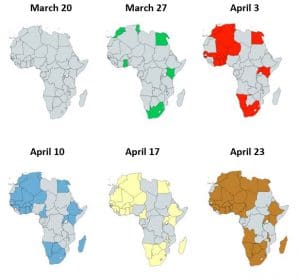

- In the past 2 weeks, 6 new countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (Chad, Malawi, Nigeria, Sao Tome, Sierra Leone and Zimbabwe) have introduced or adapted social protection programs to cushion firms and workers against losses in income. Cash and in-kind transfers are the most common, with 30 countries across the region now having a total of 68 active social assistance programs (see Figure 1 below, adapted from Ugo Gentilini’s living blog).

Figure 1. African countries with social protection programs in response to COVID-19, by date in 2020.

- Cash transfers are being adapted in three ways – expanding coverage to those outside social registries or those who are not usually eligible; increasing benefits (transfer value or frequency); and making administrative requirements simpler and more flexible (e.g. home delivery of cash for seniors or the waiving of conditionalities).

- Despite this promising change, Africa (particularly low-income countries in Central and East Africa) still lies behind other regions in terms of the number of and scope of social protection programs. Only 6 countries have available social insurance, and just 3 have active labour market programs. Governments should consider these areas for further intervention, particularly in the mid-term, as most current changes are temporary.

Education responses:

- Schools have closed in 186 countries, impacting over 90% of the world’s children. These closures, along with unequal access to replacement education services such as online learning, exacerbate existing challenges for the learning and development of children and youth in Africa (see the ILO brief on COVID-19 and the education sector). Although school closures are temporary, they have the potential to cause long-term disruptions if children do not return to school or if gaps in learning increase, which could lead to higher drop out rates and lower graduation rates later on.

- Organisations are working hard to minimise these risks. UNICEF and Microsoft have launched a global learning platform to help address the COVID-19 education crisis, and certain knowledge gaps are being filled, particularly around overcoming obstacles to remote learning and training teachers). These are crucial steps for preventing the digital divide from growing larger, but there is still some way to go in boosting connectivity and school system capacity across the region.

- Lessons are being drawn, where possible, from experiences with managing education in conflict and emergency settings (see the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) and Education Cannot Wait websites), where children cannot access normal schooling facilities and materials, and from past education responses during pandemics. This is promising for developing more overall inclusive education systems which can tailor to the variety of needs and circumstances of children living in Africa.

- Significant changes are being made to the organisation of higher education. A report by IESALC analyses the institutional responses for maintaining quality in higher education, proposing mobile phones as a key modality for distrubiting learning material in areas where internet connectivity is poor. Further recommendations are given by the Association of African Universities (AAU) for diversifying modes of delivering education and becoming more resilient against future shocks. However, the impact of the crisis on TVET and informal modes of learning, and on their role/scope for picking up current gaps in formal education systems, has been less prevalent in debates.

- The education sector plays a huge role in ensuring not only childhood learning and skill development, but also health, safety and nutrition, particularly of poorer children or those in situations of violence or conflict. A report by the Lancet highlights the likelihood of school closures increasing learning gaps between children from high- and low-income households, as well as increasing child poverty and malnutrition in households below the poverty line (either before or as a result of the crisis).

- The Human Rights Watch emphasises the need for a mix of hi-tech, low-tech and no tech solutions (e.g. interactive lessons, sending schoolwork online, or preparing and collecting/delivering paper materials) to assure continuity for all groups, especially those who already face barriers to education, such as girls, children with disabilities, and those in isolated locations or violent/neglectful homes.

- UNESCO highlights the role of home learning to compensate for losses in the classroom and promotes the use indicators to identify children living in non-stimulating or difficult environment to target interventions.

- Schools, skills, and learning: The impact of COVID-19 on education discusses the implications of the COVID-19 learning crisis at different levels (families, schools and societies), and stresses the need for coordination between these levels (both in the short- and longer-term) to maintain skill development, assessment quality and the likelihood of graduation and employment for young people.

- Although humanitarian responses to food, water, sanitation and livelihood crises are first priority during this time, INCLUDE sees education as critical for Africa to avoid reversing progress in the SDGs, given the role of education in tackling multiple development issues. In particular, managing the education sector response will have important consequences for countries’ abilities to, on the one hand, respond to changing markets and develop local industries by (re)building human capital and key skills, and on the other hand, ensure nutrition, safety and equality for all young people which affects their immediate and long-term wellbeing.

- Certain opportunities are emerging from the intensification of the learning crisis in Africa. For example, the opportunity to accelerate the adoption of technology for the purpose of learning and explore more flexible learning schedules for the future (which are useful for all children, particularly children in remote areas and children with disabilities), and to solidify health education in core curricula to increase awareness around the prevention and preparedness of diseases.

- Acknowledging the main challenges around technology, training and reaching marginalised groups enables them to be part of recovery debates from the outset, and to establish key actors and strategies for financing, delivering and leading interventions to solve them. For example, including education as an explicit part of public stimulus packages, or the roles of the private sector and civil society in finding/delivering technological solutions and promoting the education needs of vulnerable children. The ultimate goal is to ensure that all children in Sub-Saharan Africa return to school and catch up what they missed, as well as to keep momentum in education system improvements across the region.

17.04.2020

There has been a marked slowdown in the rate of new coronavirus infections in the WHO Africa region. Multiple countries have reported no new cases. Hospitals are gathering as many resources as possible, but beds are not filling at the expected rate. It is unclear whether this reflects the success of policies to curb the spread of COVID-19, a lack of testing and limited access to hospitals, or (as some put it) the ‘calm before the storm’. Societies have been urged to remain cautious and avoid complacency, which could re-accelerate the virus.

There is growing knowledge around what is needed in terms of resources (and, to a lesser extent, strategy), but major constraints remain in financing interventions, engaging communities and fostering political cooperation. Moreover, various unintended consequences of recent policies are at risk of emerging, such as leaving certain groups behind, increasing poverty and neglecting other development issues:

‘If basic livelihoods cannot be secured, a comprehensive lockdown is not practical. Poor people will prefer the lottery of infection over the certainty of starvation.’ (BBC)

The need to adjust the local context has gained importance following the initial panic phase which entailed more uniform responses. Although transmission mechanisms are the same everywhere, the disease burden, infrastructural capacity and economic vulnerability differ vastly by country. Therefore, a single set of guidelines will not suffice, and governments must act locally to minimise short- and long-term damage.

- There has been remarkable progress regarding social protection in the Sub-Saharan Africa region. Since 20 March, 22 countries have introduced or adapted social protection and labor market programs to deal with COVID-19. Nearly all of these countries have waived utility fees, 7 have implemented in-kind transfers, and 5 cash transfer programs, with some also targeting the informal sector.

- Recent experiences with food programs have concluded that cash is better than food distribution, as the latter attracts mass gatherings and creates violence between community members over rations. Advice is to introduce/scale up cash transfers more rapidly, expanding eligibility to include those who don’t normally need it.

- IDInsight published a policy brief with recommendations for social distancing in African countries, taking into consideration local social norms and practices and local economic activity. The brief pushes for adjustments to activity rather than total quarantine (e.g. in the case of public transport, limiting the number of service users, encouraging walking/cycling and imposing extra cleaning regulations) and includes special guidelines for those in unique circumstances, such as migrants returning home, the sick and the elderly. It also highlights methods of raising awareness (using multiple languages, radio or SMS where internet connectivity is poor, and communicating through traditional leaders) and ways to minimise the short- and long-term impact of social distancing (e.g. maintaining school feeding and remote learning).

- The measures discussed in last week’s news item (namely tax breaks and free services) are not financially sustainable without international assistance. Given the squeezed fiscal space in many African countries and the constraints on foreign aid, resource mobilisation is at the forefront of the crisis debate. The US has cut WHO funding, and DFID’s pledge allocated just £20 million to charities, questioning who will pick up the gap in critical NGO funding. More positively, the G20 has frozen debt, freeing over $20 billion dollars for low-income countries’ responses, and the IMF is seeking to triple concessional financing to poor countries.

- Focus on the informal sector continues, particularly regarding the intensified exclusion of the waste sector. Opponents to the lockdown stress that risk is normal in Africa, that the region is prone to crises, but insurance mechanisms to overcome these (including remittances and informal work) have been removed. In response, WIEGO has created a tracker of responses which affect the informal sector by country.

- Unintended consequences of coronavirus responses are becoming visible across Sub-Saharan Africa. Food security is a growing concern under restrictions of activity and movement. Important development issues are lacking attention due to the focus on the crisis, for example, the locust plague in East Africa; maternity care in Uganda; ongoing violence and displacement in Guinea; and malaria, TB and HIV treatment throughout the region.

- Significant emphasis is being placed on local leadership to overcome the pandemic in a way which includes the most marginalised. Community driven responses can help to increase awareness and conquer stigma among vulnerable groups. Local engagement can also provide decision makers with timely and accurate data which helps them to understand local (often fragile) contexts and assess what policies are working.

- Organisations have begun discussing the longer-term sustainability of COVID responses. The UN has drafted a set of priorities for tackling the negative impacts on each SDG goal. The World Bank has developed a sustainability checklist for policymakers to help create stimulus packages which are centred around job creation, boosting activity, future resilience and decarbonisation of the economy. It will be a critical moment to ensure inclusion when regulations are relaxed, for example by ensuring that girls return to education when schools reopen.

- Another major concern regards a human rights overreach – the need for protection through emergency armed forces and digital surveillance countering civil liberties and removing power from local authorities, which often harms the poorest and most vulnerable. The Health and Human Rights Journal examines the impact of interventions and discrimination linked to coronavirus on civil freedom and the access to crucial services (see Lessons learned from HIV and the Evolution of the right to health).

- There is an acknowledgement that we must also seek out opportunities for Africa during this hard time. There is a chance to set a ‘new normal’ involving localisation of power, more resilient and productive agricultural networks, and a renewed focus on inequality and the winners and losers of development.

10.04.2020

In the past week, a more detailed trajectory of the coronavirus in Africa has emerged (see Elephant, BBC and African Arguments for country-level timelines). The immediate impacts of the global lockdown on African economies have been analysed more factually, with reports showing which sectors are being hit hardest (see the World Food Programme and IFPRI on food and agriculture, and the SET and African Union on the trade, tourism and oil industries). Evidence on the long-term impacts remains speculative, with scenario estimates involving a high degree of uncertainty.

The WHO and Africa Centre for Disease Control (CDC) continue to play a major role in guiding the region’s pandemic response and maximising healthcare capacity. Nonetheless, with insufficient testing, many people remain anxious about the outbreak exploding in poor and densely populated areas. The question remains if governments have acted quickly and strongly enough (and have enough global support) for Africa to avoid catastrophe.

Another major development this week is the growing realisation that we need to unite and help the most vulnerable first. With so much of the world relying on suffering industries for their wellbeing, and the risk of recontamination high without a collective cure, it is clear that global solutions must start with cooperation and ensuring survival for those who have been left behind. With so many organisations attempting to share and synthesise information, INCLUDE deems it important to focus this debate.

Given the range of responses to the pandemic and the need for collective effort, we have broadened the scope of information from government policies to include responses by multiple actors. The number of interventions in Africa has increased in the past week, with some concrete steps being taken to protect citizens across Africa, both healthwise and economically.

- Policy trackers are now available for most countries in the African region. The IMF comments on various fiscal and monetary policies related to taxes, public expenditure, loans, banking fees and interest rates. The ILO also covers employment and labour policies to do with leave arrangements, workplace safety and job protection.

- The number of social protection interventions in Africa has grown, mostly in social assistance and in-kind transfers, but many countries are still to implement these measures, and some of the distributive mechanisms are being questioned in order to help transfers reach the most vulnerable.

- SET ODI has published a breakdown of bi-lateral, multilateral and private donor responses to the crisis along with their intended destinations and purposes. Devex has also created an interactive funding platform. Despite the range of contributions, a report by UNCTAD argues that the total value of donor receipts does not nearly compensate for expected losses in the developing world, and that much more is needed to aid recovery.

- There have been various examples of interventions to fulfil basic service needs. The Guinean government announced that it will cover water and electricity costs for the next 3 months. In Ghana, rents have been frozen along with prices on pharmaceuticals and basic necessities, and public transport will be delivered free. Numerous international organisations, development institutions, NGOs and private sector initiatives are working hard to expand medical supplies and food aid corridors in the African region.

- The Mckinsey institute’s regional analysis for Africa poses important questions for forthcoming interventions on the trade-offs between public health and economy, between the short- and long-term, and between targeted and broad-based support.

The debate on vulnerable groups has gathered pace this week. A major question is who is benefiting from current interventions, particularly those aiming to protect income and basic services, and who are left unprotected? For example, people living in poor, informal and fragile settings, often in overcrowded settings with limited access to sanitation, healthcare and digital infrastructure, cannot afford to give up work and do not benefit from subsidised wages, unemployment benefits or free basic services. This has driven discussion around alternative responses which are more appropriate in local African contexts.

- Update: ILO Monitor 2nd edition: COVID-19 and the world of work. Africa has seen a 4.9% decrease in working hours, and 26.4% of regional employment is in sectors suffering from significant output decline. These figures may be lower than other regions, but the document also highlights the much higher proportion of unprotected workers in the African region (71.9% informality rate in non-agricultural work and limited social protection coverage) which could lead to much greater impact on livelihoods and poverty.

- Issues around informal work have been raised by multiple organisations, including IDS; The Conversation; Bloomberg; IFPRI; WIEGO; and IIED. Informal work is often a way for individuals to overcome the incapacity of state / formal institutions and ensure their own livelihoods. Under lockdown, this option becomes unavailable, and many SMEs do not benefit from tax relief, formal wage subsidies and digital money schemes. Decision makers are being urged to find alternative approaches to containment which suit the African context (such as sequential lockdown or group quarantining) rather than copying western methods.

- Adding to the debate on gender inequality, which has focused on the high representation of women in care roles, front line positions and vulnerable work, evidence reveals a growing incidence of domestic violence against women and increased barriers to resources for SRHR driven by the channelling of critical resources to COVID needs and the restrictions on travel and trade.

- The realisation of unintended consequences has caused concern over how countries, particularly in low resource settings, will maintain care for HIV sufferers and people with disabilities and other health conditions over the coming period.

- Conflict areas continue to be of large concern, due to lack of coordination, extreme inequality, undermined public infrastructure and limited data transparency.

- Case studies from Nigeria, Kenya, Burkina Faso, SA, Zimbabwe (also Uganda) highlight the exacerbating effect of the crisis on existing inequalities and the fulfilment of basic human rights.

An aritcle by Devex summarises research which states that the current economic fallout could plunge up to 580 million people into poverty and represent the ‘first increase in global poverty since 1990 and have grave implications for achieving development objectives such as the Sustainable Development Goal‘. This makes efforts for inclusive development more important than ever.

Education

- The World Bank shares weekly updated responses in the education sector; as of April 3, 39 countries in Africa have closed their schools, many without the option for distance learning.

- A report by K4D identifies knowledge gaps for the education sector during the current crisis, based on evidence from past disease outbreaks. The report highlights major gaps on how to support students through distance learning and IT-enabled learning, how to train teachers remotely and how to support learners with disabilities and learners in refugee situations.

- The Lancet carried out a rapid systematic review of school management practices during pandemics, using data from the SARS outbreak in China, Hong Kong and Singapore. The study concluded that certain social distancing methods other than school closure are more effective at containing viruses and less socially disruptive.

Governance and leadership

- The ODI published a series of briefing papers on adaptive leadership and the scope for bridging science, policy and practice during this time in order to establish collective and flexible decision-making.

- The USIP identifies key lessons for governance based on past outbreaks in Africa, including the importance of local leadership, maintaining other public health priorities, the need to avoid blame and stigma, and the need for broad social coalition beyond government. Contrary to this, a debate from LSE suggests that many lessons from the past cannot be applied in this unique context and the optimal strategy is to learn as we go.

- An ODI research report from 2019 on risk-informed development stresses the need to for decision-makers to understand the complexity of multiple risks and the exact trade-offs being faced, to specify responsibilities, and to account for feasibility, resource constraints and risk tolerance.

03.04.2020

For general situational overviews, Africa News and African Business provide regular updates on policy changes, public reception, funding measures and donor support across Africa, while the World Health Organisation produces weekly situation reports and risk analyses for the region, including efforts to expand healthcare capacity and surveillance.

So far, the majority of information on the impacts of COVID-19 takes the form of blogs and opinion pieces by researchers, policy makers and development agencies and practitioners, often attempting to draw lessons from past experience and apply them in this unique context. A few reports are already available which use economic and health data to estimate the social and economic damage caused by the outbreak and related recession, but such reports tend to take an aggregate growth approach and do not yet address the issues of inequality and inclusion, hence the need to stimulate this debate.

Armed with foresight and experiences from Ebola, many governments have acted quickly to try and suppress the virus through lockdown measures and mobilising healthcare resources. However, African countries have some of the lowest healthcare capacity, weakest infrastructure, and highest levels of debt and poverty globally, which increases their vulnerability and limits policy options to respond to this emergency. Poor data availability makes it even harder to understand the severity of the problem and act effectively and in time. Here, we summarise some of the latest evidence on how African governments and foreign donors are dealing with the crisis as it unfolds, and what major challenges they face.

As Africa is the last continent to be hit by the virus, we are yet to see many of the measures different governments will implement, and how inclusive they will be. Economic policy packages depend on factors such as funding, debt relief and social acceptance. However, some of the emergency responses are already being evaluated in terms of their impact.

- Measures taken to curb the spread of COVID-19, especially lockdowns, curfews and closures which limit the movement of goods and people, have already caused major disruptions in the supply chains for food, fuel and other raw materials, and led to income and job losses in the tourism and service sectors. Since many African nations depend on these industries, these lockdowns have severe implications for food security, poverty, trade and investment.

- Various international organisations, including the World Bank, IMF and the UN have launched emergency support operations and financial stimulus packages aimed at helping developing countries to weather the storm of the virus and reboost their economies. However, there is skepticism over whether these pledges are sufficient to help Africa recover,.

Currently, social protection lies at the centre of the debate around securing income and supporting basic needs. The number of countries implementing or expanding social protection measures worldwide has almost doubled during the COVID-19 pandemic and it is still increasing. These are mostly middle- to high income countries. As of March 27, 6 African countries (of which 3 Sub-Saharan) have scaled up existing social protection programs or implemented new ones (for weekly updated figures: www.ugogentilini.net).

- Berk Özler’s informative blog, ‘What can low-income countries do to provide relief for the poor and the vulnerable during the COVID-19 pandemic?, states that low-income countries have to rely on their existing social protection systems and safety nets, using for example workfare programs, cash for public works, or unconditional targeted or universal cash transfers.

- This IMF blog ‘Limiting the fallout of the Coronavirus with large targeted policies’ suggests that government spending should focus on health systems first, and deal with the economic fall-out of restrictive measures taken to limit the spread of the virus. It argues for a targeted approach using cash for households and businesses that are affected by the pandemic.

- ‘Social protection: Protecting the poor and vulnerable during crises’ argues that social protection measures are often the first line of defense for poor and vulnerable groups during crises, and scaling up these measures in times of crises, through partnerships on different levels, could be of paramount importance.

- In ‘Social protection systems failing vulnerable groups’ the ILO warns that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic for the most vulnerable in low-income countries are exacerbated by limited health insurance coverage and access to national health services; and the fact that many workers cannot take sick leave or cope with unexpected emergencies.

- In a Webinar on 31st of March 2020, Ugo Gentilini and Francesca Bastagli discuss Universal Basic Income as a social protection measure to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, taking into account the availability of adequate and inclusive delivery systems (digital, cashless or contactless); methods of determining eligibility (balancing outreach and efficiency, also depending on adequate demographic information); financing or funding (to make Universal Basic Income a sustainable form of social protection in a post-COVID-19 pandemic society. One of the possibilities of Universal Basic Income as a COVID-19 response is to be bolted on to existing social protection programs, making use of systems of delivery and demographic information.

- Multiple resources look at models of adaptive social safety net programs already in place in Burkina Faso, Niger and the Central African Republic, as well as other cash-based interventions, notably GiveDirectly and the BRAC graduation model.

- In ‘Lessons learnt from the Ebola crisis in West-Africa: a focus on Cash Transfer Programming’, the Cash Learning Partnership points out that Cash Transfer Programs could be applied as support for transport or resettlement, incentives for affected people to stay home, or health workers to continue working, or to support and revitalize markets and livelihoods. The article stresses the importance of assessing the context and impact on market systems, as well as the capacity and availability of service providers and acceptance of government modalities.

- ‘Can public works help fight Ebola in the Democratic Republic of Congo?’ explores how implementing major public works programs generate community engagement that is essential to curtailing an epidemic, especially in an already conflict-affected area, where overlapping and sequential crises confound an epidemic outbreak.

While a lot of attention has been given to the consequences of coronavirus for societies as a whole (including rising unemployment, declining GDP growth, and increased mortality), the debate on vulnerable groups is much quieter. Understanding the extent to which different groups are at risk, and how certain policies and programme can protect and support them, is crucial for promoting effective and equitable interventions and preventing them from being left further behind.

Vulnerable groups include those living in poverty, informality, conflict and fragility, often in overcrowded settings with limited access to sanitation and healthcare, who cannot afford to give up work and who do not benefit from subsidised wages or unemployment benefits. It also includes young people, who may struggle even harder to find decent work in a collapsed global economy, women, who lack decision-making power and are disproportionately represented in healthcare, childcare and vulnerable work, and other marginalised groups who may not be able to access the resources they need for their wellbeing.

- The ODI blog ‘From pandemics to poverty: the implications of coronavirus for the furthest behind’ discusses how poverty, malnutrition and existing disease compound vulnerability to the virus, and how lockdown measures can harm those living and working informally.

- ‘The Next Wave: U.N. and relief agencies warn the coronavirus pandemic could leave an even bigger path of destruction in the world’s most vulnerable and conflict-riven countries’ from the Foreign Policy website explains the potentially devastating impact of COVID-19 in situations of conflict and humanitarian emergency, due to the lack of sanitation facilities, overcrowded refugee camps, strained foreign assistance and restricted transportation of goods and aid workers.

- ‘COVID-19 and the world of work: Impact and policy responses’ is an important report by the ILO estimating ‘high’ and ‘low’ scenarios for changes in employment and labour income in the context of coronavirus. The report also looks at how these impacts on work will be felt strongest by young, old, female, migrant and unprotected workers, and outlines essential policies for mitigating the damage to jobs and income.

- In ‘Coronavirus and poverty: we can’t fight one without tackling the other’, Poverty Unpacked highlights the deeper and longer lasting impacts of decreased work, school closures and health shocks on the world’s poorest, and stresses that failing to help them could be universally damaging.

- ‘When face-to-face interactions become an occupational hazard: Jobs in the time of COVID-19‘ by Brookings analyses how job and income losses are occurring mostly in sectors where home-based work is impossible or which require face-to-face interaction, such as agriculture, manufacturing, tourism and retail trade. These occupations are disproportionately common among low-paid and low-skilled workers.

- ‘How Will COVID-19 Affect Women and Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries?’ by the Centre for Global Development tackles the particular challenges faced by women in overcoming the crisis. A major issue is the underrepresentation of women in leadership roles involved in responding to the outbreak and protecting girls and women.

- ‘COVID-19 control in low-income settings and displaced populations: what can realistically be done?‘ by HHCC casts doubt on the effectiveness of lockdowns, quarantining and social distancing in situations where testing and surveillance are limited and dependence on exports and face-to-face work is high, and instead support the approach of locally shielding high-risk individuals.

- ‘COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak‘ by the Lancet discusses gender imbalances in mortality and vulnerability due to the dominance of women in front-line care roles and vulnerable employment, as well as their lower decision-making power to protect resources for girls and women (sexual and reproductive health). Perpetuating gender inequities.

Most countries in Africa are in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is premature to conclude how it will shape African countries in the mid- to long-term. Consensus is that it is not a case of if, but when, how, and how badly the African region will suffer, which makes debates on protection and inclusion crucial. The adverse effects of the disease will likely vary between and within countries, perhaps mirroring existing variations in income, wealth, inequality, poverty, infrastructure and access to public services. Organisations are beginning to think about challenges and opportunities for sustaining important sectors like healthcare and education and reviving markets.

- ‘Fighting COVID-19 in Africa Will Be Different‘ by the Boston Consulting group highlights certain advantages for Africa (its high youth population and increased preparedness since past outbreaks) but warns how unless responses are inclusive, they will not be successful.

- A Brookings blog, ‘Do countries have immune systems? 5 lessons from fragile states to help fight the coronavirus’, corroborates the view that although the poorest and most vulnerable will be affected most severely by the current global situation, helping them first is key for recovery. In other words, inclusivity is the only option.

- ‘Educational challenges and opportunities of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic‘ and ‘Managing the impact of COVID-19 on education systems around the world: How countries are preparing, coping, and planning for recovery’ by the World Bank discuss the poverty implications of interrupted learning, increases in school dropout and loss of school feeding on top of the existing learning crisis. They also remark on how options for remote learning are less feasible in poorly connected regions, causing concerns over their ability to sustain education systems and graduate students on time.

- ‘Epidemics and the health of African nations’ by Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (MISTRA) explores how three recent epidemics have been combated in Africa, and how inclusive responses require multi-sectoral cooperation, timely action, sufficient financing, and prevention in the future depends on reliable and inclusive health insurance, technological innovations and the removal of institutional hierarchies.

- How coronavirus is accelerating a new approach to international cooperation‘ by the ODI, ‘Opinion: Aid in the time of COVID-19 — 3 things donors can do now’ by Devex challenge the roles of donors in the efforts towards sustainable recovery, and stress the importance of thinking and working internationally to prevent reoccurance.

Open to contributions

Regularly updated resources and events to keep an eye on:

- Cash Learning Partnership COVID-19 page features information and guidance for Cash-Based responses to COVID-19

- WIEGO Informal Workers during COVID crisis is addressing informal workers’ issues during the pandemic

- Ugo Gentilini’s Weekly updated Social protection during COVID gives a weekly updated overview of social protection measures during the pandemic

- The WHO situation update provides information on the virus trajectory across the African region

- The ILO and IMF have developed economic policy trackers which show how each country is tackling the crisis

- The African Evidence Network posts a series of informed rapid reviews on the implementation and impact of COVID-related policies

- The World Bank database on trade flows of crucial medical and sanitation equipment and health sector capacity by country

- Socialprotection.org: Social protection responses to COVID19 features an online community and discussion between experts, a pool of resources and weekly webinars and items regarding social protection during the pandemic

- Institute of Development Studies – Responding to Covid-19 – the social dynamics