Policy makers in Rwanda are targeting formal financial inclusion (“having a financial account”) as part of the strategy to alleviate poverty. Our research shows that the actual use of financial accounts should become the focus of policy. Background interviews with local officials revealed their believe that individual characteristics are not important for the formal decision to accept an individual as an account holder at a financial institution. Our analysis, however, supports the importance of gender for the use of bank accounts by the self-employed in the informal sector – with clear implications for targeting policies.

During the summer of 2017 we studied financial inclusion of street vendors in the Nyarugenge District (Kigali, Rwanda), a group of underprivileged that very often cannot be reached by traditional surveys or a census. Street vending is prohibited in the Kigali, Rwanda Nyarugenge District, and during the field work several raids by local security agencies were observed. Just a few weeks after the field work, street vending was officially forbidden. Our fieldwork offers a unique and no longer existing opportunity to survey street vending as a truly informal activity in this area. The peer reviewed publication of our innovative multimethod field research appeared in Journal of African Business.

Policy makers need to focus on actual use

Having a financial account is an important policy issue for poverty reduction in Rwanda, where most of the small businesses (tailors, masons, vegetable sellers, welders, and so on) are in the informal sector and run by people with no or limited formal education. A recent Finscope survey finds that the government’s goal to accomplish 90% of ‘financial inclusion’ by 2020 is realistic and attainable.

The government’s target, however, relates to de jure financial inclusion, that is: formal financial account holdership. But simply having an account is not what matters for effective poverty reduction. In our sample the majority of financial account holders does not use the financial account frequently: 57% accessed it once or less a month (half of these accounts have been inactive over the past 12 months). Our findings point out the need for the government to reformulate its policy in terms of actual use (de facto inclusion) and our investigation indicates which tools could be useful to achieve that target.

Individual characteristics do matter for use of an account

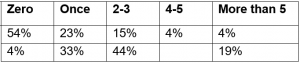

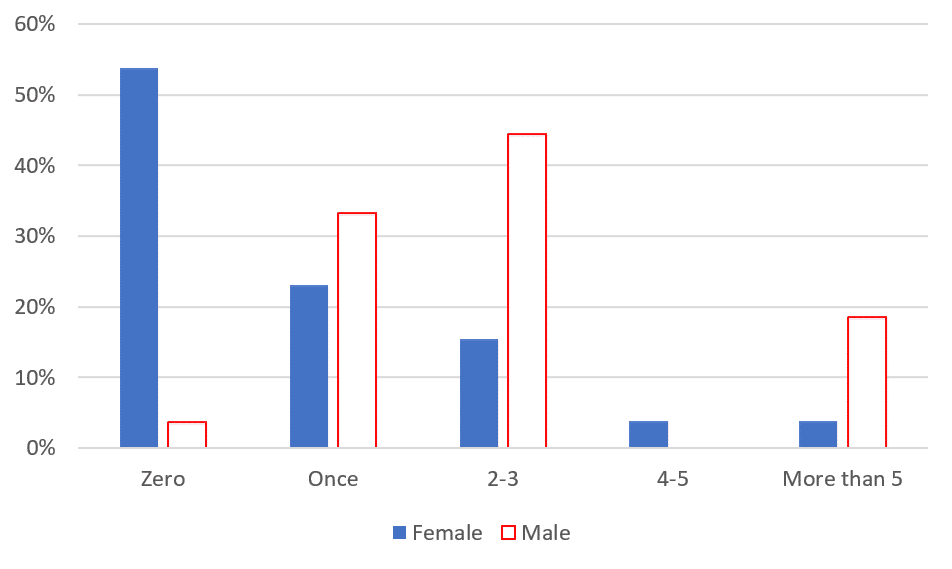

We have collected several individual characteristics of the respondents to our survey including gender, age, marital status, and education in order to be able to test if individual characteristics matter for being formally and/or de facto financially included. In our analysis we also control for weekly sales and four types of products that were traded (edibles, clothes, shoes and cosmetics). Gender turned out to be the single most significant driver of de facto financial inclusion (Figure 1) and this was confirmed in our ordered probit model (a higher level of education is associated with a higher frequency of use, but not with formal financial inclusion). Policies supporting female financial inclusion would thus seem to be necessary to correct this imbalance.

Figure 1: Frequency of use of an account by gender

Financial infrastructure is key

The presence of a financial institution in the home location of the street vendor is the most significant determinant identified by our research. From a policy perspective this underlines the importance of a good financial infrastructure: the economic geography of financial inclusion is important. Being close to a financial institution is associated with better financial inclusion. The importance of geography and location has also been established by earlier research on the differences between urban and rural areas, but our results are more specific. According to our findings the driver is the availability of a financial institution in the street vendor’s hometown, thus providing policy makers with a concrete tool to improve financial inclusion in Rwanda.