The decency of a job is not only defined by the fairness of the income earnt. It also encompasses dignity, personal and professional development, job security, a healthy work environment, and social protection. In the Rwandan context, the jobs that are available, often in the informal sector, are not aligned with the official ILO definition of decent work. The young Rwandans who participated in the webinar hosted by INCLUDE on what and when a is job decent are challenging the perception that only ‘white-collar’ jobs in the formal sector are decent, as many have been able to find decent work in the informal sector. According to youth advocates, to make more jobs in Rwanda decent, more quality jobs need to be created in both the public and private sectors. Moreover, it is necessary to adjust the business environment to better accommodate young entrepreneurs. Looking at the gender dynamics, more training on the importance of equal pay and fair treatment is needed to address gender inequalities in the labour market. Finally, a change in mindset is required to challenge the perception that only white-collar jobs are decent. The decency of work is really a personal choice.

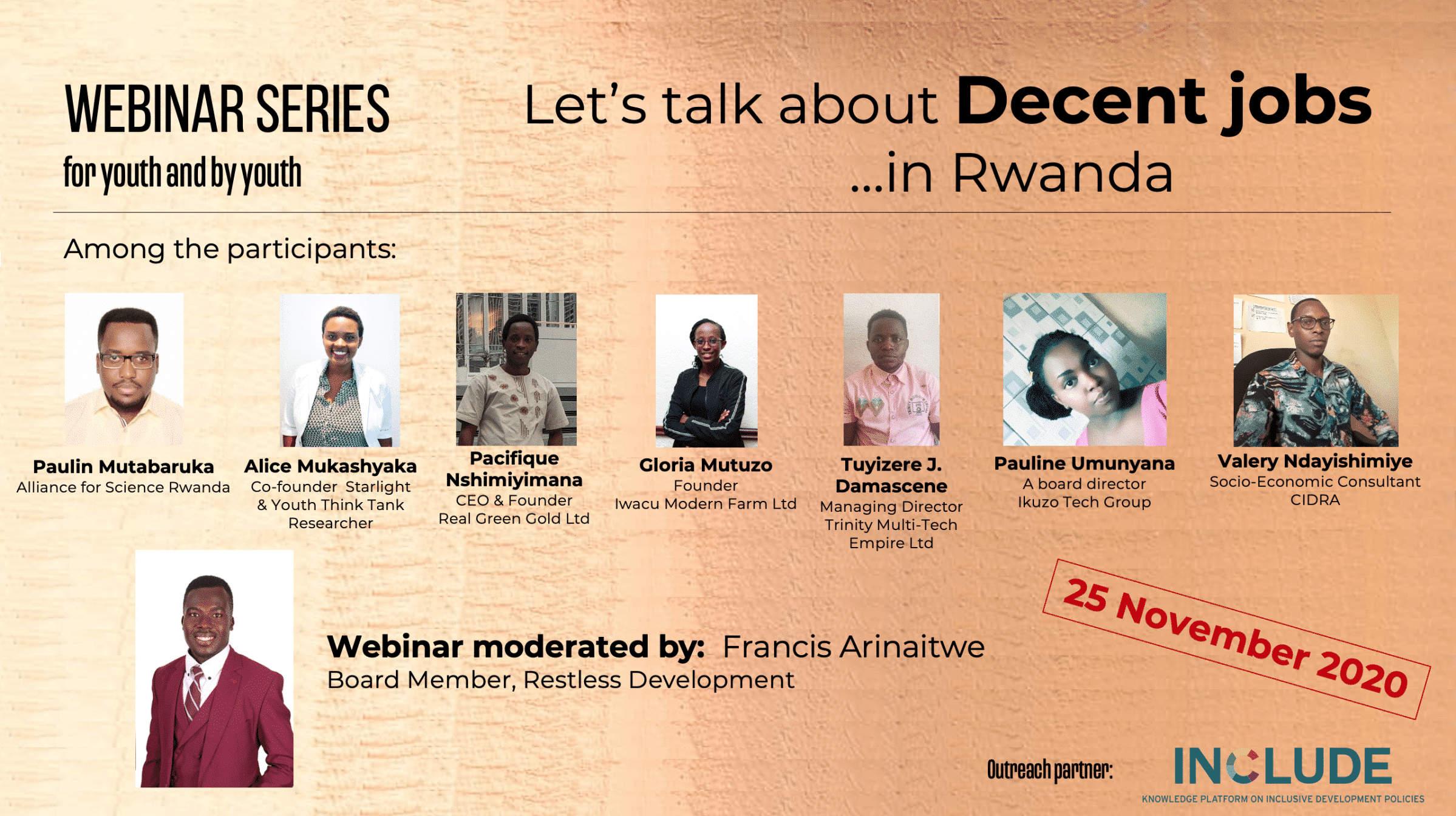

On 25 November, INCLUDE hosted the second webinar in the series on youth voices across Africa, on what and when is a job decent. This webinar series was initiated by Francis Arinaitwe, youth leader and board member of Restless Development Uganda, and organized in collaboration with INCLUDE. The aim of the series is to bring together youth from different African countries, including Uganda, Rwanda, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia, Ghana, Nigeria, Egypt, and Tunisia, to break down the official ILO definition of decent work and reflect on how it resonates with youth’s own understanding of decent work in their respective countries. In this second session it was the turn of the highly ambitious and driven youth from Rwandan to reflect on the two main questions:

- What does a decent job mean to youth in Rwanda?

- What is needed in Rwanda to make more jobs decent?

What does a decent job mean to youth in Rwanda?

The decency of a job depends on receiving a fair income (the financial freedom to sustain yourself and your loved ones) and having a passion for the work that you are doing. Receiving a good salary on its own is not sufficient. Job security, dignity, social protection and a healthy work environment are equally important, according to the youth participants from Rwanda, although the extent to which these criteria are satisfied may vary and may not always be entirely fulfilled. Moreover, a healthy work environment should not only entail good physical working conditions, but also good interpersonal relationships within the workplace. The workplace should be less hierarchical, as this gives employees more confidence in voicing any concerns that might arise. In addition, it would enable employee to think for themselves, instead of merely doing what is asked. As such, employees’ personal and professional development should also be considered when evaluating the decency of a job.

The decency of a job is ultimately for an individual to determine and, in practice, it is not always aligned with the official ILO definition of decent work. In the context of a labour market characterized by competition and a rising unemployment rate, the participants indicated that the ILO definition is somewhat disconnected from the reality on the ground for most Rwandan youth. For example, there are many young people in Rwanda who turn to the informal sector for employment – some because they are unable to find work in their field of study or interest and they need ‘any job’, others as a career choice (e.g. to be self-employed). In both cases, it is possible for them to find a decent income and dignity. As the principles penned to describe decency are not equally relevant to everybody, the distinction between formal and informal work is, therefore, not the most relevant. Overall, the current official definition, according to youth, does not adequately capture cultural norms and realities. It is much more important to look at the impact of a job and not judge it outside its (cultural) context.

What constitutes a decent job differs for men and women. Due to gender constraints in the labour market, many young women in Rwanda are overrepresented in the informal sector. This overrepresentation is also dependent on the sector. According to the participants, societal norms and expectations dictate that certain sectors are considered to be ’female’ and others ’male’. For instance, hospitality and tourism are seen as ‘female sectors’, while mining is regarded as a ‘male sector’. Inter-sector inequalities persist in some sectors, for instance, in agriculture. While women are involved in most agricultural work in the field, they seldom own the land. Such inequalities are much less visible in the IT/tech sector. Despite an increasing number of women in lead roles in the government and corporations, the wage gap between men and women remains a cross-cutting issue. Training about the importance of equal pay and fair treatment for both employers and employees, men and women, should be more broadly introduced to effectively address this issue. Finally, young women in Rwanda need to be more aware of their value and improve their negotiation skills when discussing expectations about their salaries.

What is needed in Rwanda to make more jobs decent?

First and foremost, more quality jobs should be created for both men and women in the public and private sectors in Rwanda. This will not only make the job market less competitive, it will also allow Rwandan youth to search for a decent job and not ‘any’ job (which is often the case now). Secondly, the private sector in Rwanda should be stimulated to offer quality jobs. This can be done either by providing an incentive scheme to encourage employers to comply with the parameters of decent work, as set by ILO, or through specifically-designed and enforced compliance overseen by dedicated institutions or the government. Thirdly, according to the participants, decency lies in self-employment. Many young Rwandans are becoming entrepreneurs and establishing their own ventures. It is important to accommodate this trend by creating a friendly business environment for start-ups and guiding policies, because through self-employment young entrepreneurs can create decent work for themselves as well as for those whom they employ. Finally, a change in mindset is needed. It is no longer productive to ascribe a certain sector of the labour market to a specific gender. We also need to change society’s perception that only white-collar jobs are decent. At the end of the day, whether or not a job is ‘decent’ is a personal choice.

The next webinar will be organized with youth in Kenya.