Young people struggle to find jobs. Landing that first job is particularly challenging even for youth with quality education. In 2016, 100 young women under 25 in the Gjakova and Lipjan municipalities in Kosovo were seeking their first opportunity after completing university-level education. They enrolled in the World Bank’s Women in Online Work (WoW) pilot, a training program that aims to equip beneficiaries with the skills they need to find work in the online freelancing market. Within three months of graduation, WoW’s online workers were earning twice the average national hourly wage in Kosovo. Some graduates even went on start their own ventures and hire other young women to work with them.

This is but one example of the promise that digital jobs hold. Technological advancement has given rise to a growing digital economy which continues to create new forms of work, transforming the employment landscape. Yet, joblessness persists. In 2017, approximately 65 million young people aged between 15 and 24 were unemployed. Youth labor force participation rates are on the decline globally, and over 22% of young people are not in employment, education or training (NEET). And women continue to lag behind men. The success of the WoW pilot goes to show that reaping the benefits of the digital economy requires appropriate interventions.

Developing gender-inclusive digital jobs programs for youth is the subject of a new report, Digital Jobs for Youth: Young Women in the Digital Economy by Solutions for Youth Employment (S4YE). S4YE is a multi-stakeholder coalition housed in the Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice of the World Bank. The report was a joint exercise by the S4YE partnership, and was co-authored by The Rockefeller Foundation, Plan International, RAND Corporation and the World Bank. The report develops a new typology of digital jobs, draws on real-world experiences of S4YE partners, and provides operational recommendations on designing and implementing gender-inclusive interventions.

The new typology shows that “digital jobs” range from microwork-type jobs that need very basic ICT and cognitive skills to more formal ICT sector jobs like network administration that require advanced digital and analytical skills. Other types of digital jobs included are BPO sector jobs, virtual freelancing, digital platform-linked jobs, digital entrepreneurship or public sector driven jobs. Each category requires a different type of skill set. Using this typology, the report suggests, could help policy-makers assess existing levels of demand for skills and identify opportunities to stimulate job growth for a variety of target groups.

For example, if a policy-maker would like to focus on digital job creation for rural women with limited skills, then microwork opportunities might be one category with the highest potential economic and social benefits. On the other hand, if the policy challenge is to create quality jobs for unemployed or under-employed college-educated youth, then investing in digital entrepreneurship might hold the most potential. Finally, if stimulating agricultural productivity and promoting rural incomes is high on the policy agenda, policy-makers may find it valuable to support new solutions using digital platforms that focus on SMEs.

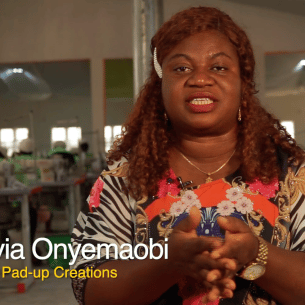

Digital Jobs for Youth extracts insights from 19 case studies based on past and ongoing employment programs implemented or supported by S4YE partners that connect youth with digital job opportunities. After reviewing program findings with youth beneficiaries, entrepreneurs, digital jobs program staff, and firms hiring youth, the report identifies 8 main challenges practitioners experience and present 20 high-potential strategies to overcome them.

For instance, the report finds that, despite best intentions, several digital jobs programs struggled to recruit female youth beneficiaries. Family and household responsibilities impose severe time constraints, preventing them from attending training programs. Additionally, young women spend a disproportionate amount of time managing household and family responsibilities, when compared to young men. This makes it harder for them to engage in activities that will generate income or further their education.

In Kenya, Digital Divide Data (DDD)—a grantee of The Rockefeller Foundation’s Digital Jobs Africa initiative—offered face-to-face and online learning to provide youth with the flexibility to complete assignments according to their own schedules, while developing teamwork and communication skills. Plan International’s Saksham project in India used creative outreach methods including project announcements on cars and strategically located information kiosks, and social media ads with powerful girl-centered stories, for recruiting young women into their program.

Share or workers using digital skills by sector, selected countries

Women also struggle to overcome stereotypes about their abilities and hiring biases of prospective employers. In response, Laboratoria, a coding bootcamp for women based in Peru, Chile, Mexico and Brazil organizes Talent Fest, a 36-hour hackathon. Participating companies provide a real web development problem they face, and students brainstorm, problem-solve and present solutions. This in-person participation gives companies the chance to see first-hand how the young women work, providing crucial insight into finding the right fit for openings.

Whereas supply-side skills-building programs are important, they are not sufficient for connecting youth with work opportunities. For digital jobs programs to succeed, they must also address the demand-side and make it easier for firms and entrepreneurs to create more and better jobs for young women.

The World Bank’s Digital Jobs for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) project presents an example of how governments can integrate gender-inclusive supply- and demand-side approaches to boost youth employment. Digital Jobs for KP takes an integrated approach that brings together digital skills training programs while also offering a package of incentives to make it easier for domestic and international firms to open businesses that hire local youth.

Governments, donors, non-governmental organizations, and private sector companies are increasingly realizing the social, economic and political benefits of closing both the gender digital divide and the gender gap in youth labor force participation.

With a more robust program design, practitioners can continue to scale impact and bring more young women in to the digital economy. Digital Jobs for Youth: Young Women in the Digital Economy provides the tools to help them do so effectively.

You can learn more about the Solutions For Youth Employment (S4YE) multi-stakeholder coalition and their activities via this link and follow the World Bank Jobs Group and S4YE on twitter: @wbg_jobs @S4YE_coalition