Not all youth employment programmes in fragile and post-conflict settings contribute to peace, even if they create jobs. It is important for funding agencies to decide prior to designing such programmes whether job creation is their main goal or if employment is a mean to achieve peace. To achieve impact beyond employment, there is a need to focus on decent jobs, as well as conduct in-depth analyses of labour markets and the political economy, which must inform programmes’ theories of change and monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL) frameworks. Donors should remain open to programme adaptation and encourage iterative learning for improved practice. Finally, connecting the body of knowledge on youth employment programmes and programmes in fragile and post-conflict settings can teach us important lessons on how to design more effective youth employment programmes for peacebuilding in specific fragile contexts.

These were some of the main points raised by Valeria Izzi (PhD) and Marjoke Oosterom (PhD) during the plenary (webinar) session on ‘Promoting Decent Employment for African Youth as a Peacebuilding Strategy’ organized by INCLUDE for the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Sustainable Economic Development Department (DDE) on 9 June. The objective of this plenary session, which attracted over 50 participants, was to share important reflections and a set of recommendations on youth employment programmes in fragile setting. The presentation was based on the findings from the evidence synthesis paper of the same name by Valeria Izzi prepared within the frame of the ‘Boosting decent employment for Africa’s youth’ partnership between INCLUDE, the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) and the International Labour Organization (ILO), under the umbrella of the Global Initiative on Decent Jobs for Youth.

Youth employment programmes are commonly used as a tool to promote peacebuilding in post-conflict and fragile settings. Yet, despite their popularity, evidence of impact is scant. The rather disappointing results of these programmes cannot be blamed only on contextual factors and implementation challenges. Programmes have long been based on the assumption of a straightforward correlation between employment and security. However, based on extensive evidence review, it is increasingly evident that a narrow focus on employment status is reductive and that there are other factors at play. To improve youth employment programmes and let them contribute to the peacebuilding process in fragile and post-conflict settings, Drs Izzi and Oosterom shared the following insights and recommendations.

Context analysis

The quality of jobs created matters, as well as who gets which jobs, and how. The assumption that on the macro or regional level the unemployed cause violence is not supported on an individual level, as illustrated by one of the examples in Dr Izzi’s paper and highlighted by Dr Oosterom during the plenary session. In the area where Boko Haram is active, many youth face unemployment, yet only a few join this violent path. Therefore, youth employment programmes must look at the experience of work more broadly, what kinds of jobs are available and what they actually provide participants with (livelihood, prospects, security). To achieve this, we must acknowledge that labour markets are also political arenas, and this should be reflected in the context analysis prior to programme design.

Context analysis (that includes economic, political economy and conflict) is crucial to good programming; yet, so far, youth employment programmes are rarely accompanied by such in-depth analyses. Unfortunately, youth employment programmes can be real assets for political regimes and non-state political actors. Political dynamics interfere with local labour markets and, consequently, youth employment interventions can be used to strengthen the political capital or support base of the ruling party, (former) combatants or other ‘big men’ (as seen in Nigeria, Zimbabwe and Ethiopia). Youth interventions can feed into the patronage networks of these actors.

Implementing agencies must be mindful that fragility comes in many shapes and forms. The more autocratic regimes (i.e. Egypt, Tunisia, Zimbabwe and, increasingly, Uganda) are more likely to appropriate an intervention (by influencing who gets to participate, who receives grants, where an intervention can operate, or by requiring ‘fees’ from participants). Where power is more diffused, different kinds of problems appear, such as weak institutions. In the case of cyclical violence between communities in Nigerian Middle Belt States, a problem can be that participants are not fairly drawn from different communities, fuelling perceptions that the programme is biased. Adequate context analysis in fragile and post-conflict settings requires expertise on political economy analysis and conflict dynamics. Firstly, it should be determined whether an employment programme is the best solution in the given context or a different type of programming would fit better at that stage. Secondly, once implementation starts, the changing contextual dynamics should be monitored closely. Therefore, in-depth context (economic, political economy and conflict) analysis must take place before programme design, as well as during the implementation phase.

Programme design and risk analysis

The evidence shows that it is important to distinguish between youth employment programmes in fragile and post-conflict countries and youth employment programmes for peacebuilding. The main goal of the former is job creation, while the latter see employment creation as a means to promote peace. Both types of programmes must be conflict and fragility sensitive, but youth employment programmes for peacebuilding cannot assume that jobs alone will make society more peaceful. To achieve peace, a suite of interventions and approaches is required, including components of governance and peacebuilding. Such interventions need complex design, implementation and MEL frameworks.

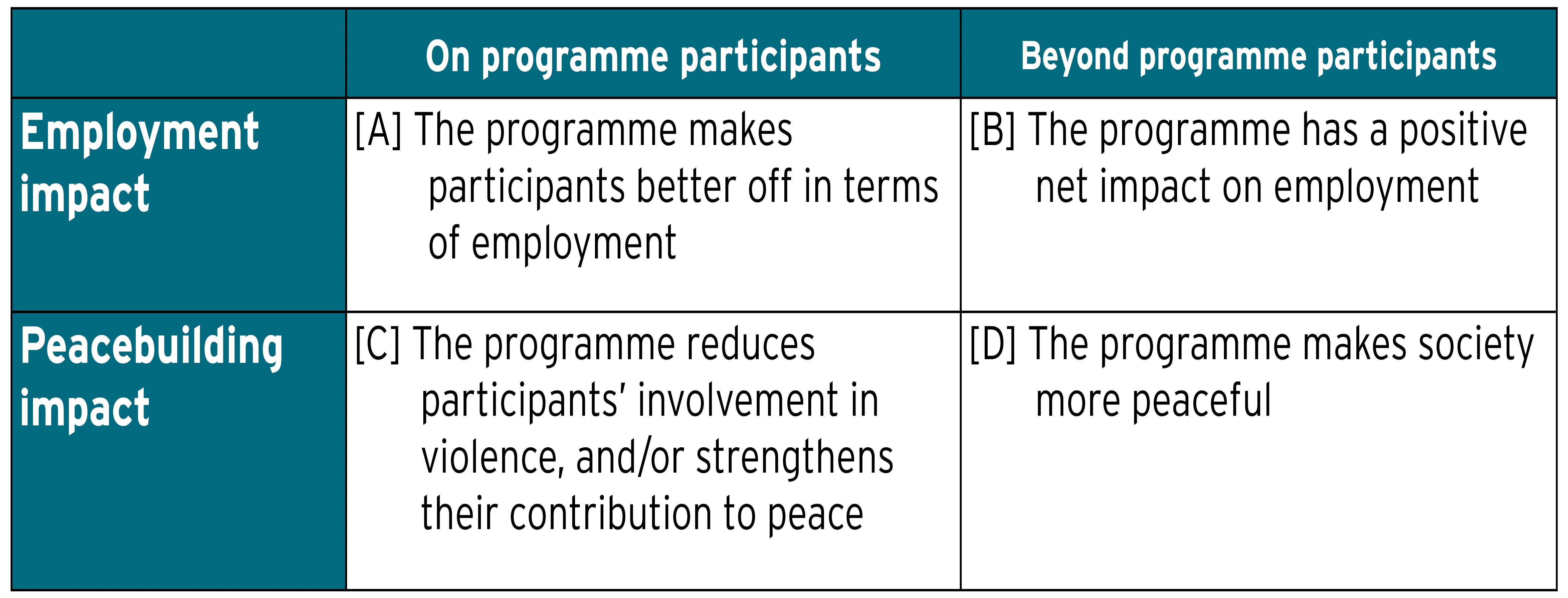

It is recommended that youth employment programmes implemented in post-conflict and fragile settings distinguish between two different types and levels of impact: impact on employment and peacebuilding and impact on programme participants and society at large (see Table 1). The 2016 report ‘Jobs aid peace’, which conducted an extensive literature review with the meta-analysis of over 400 programmes implemented by four main multilateral agencies in post-conflict and other fragile settings between 2005 and 2015, revealed that most evaluations of youth employment for peacebuilding programmes are able to only assess the impact of employment on participants ([A] in Table 1) and ignore the possibility of deadweight loss effect (where programme outcomes are no different from what would have happened without the programme); substitution effect (where workers hired in a subsidised job are simply substituting for unsubsidised workers, who would otherwise have been hired); or displacement effect (where a firm with subsidised workers increases output, but displaces/reduces output by firms that do not have subsidised workers). These programmes simply assumed that the jobs created would have a catalytic effect on making society more peaceful. However, what should also be considered in official evaluations is how impact on participants actually translates into impact on society in terms of peacebuilding in fragile contexts and whether the programme has any unintended negative effects. This can be done by preparing a detailed risk analysis of the programme capture and other negative externalities, such as reinforcing existing grievances.

Table 1. Different levels of impact of youth employment programmes in post-conflict and fragile settings[i]

Clear criteria and transparent processes for the selection of the participants/beneficiaries in youth employment programmes is equally important. One of the fundamental weaknesses of youth employment programmes is their broad selection criteria (e.g. ‘vulnerable youth’, ‘youth at risk’), which can apply to the majority of youth. In practice, jobs created through youth employment programmes have the capacity to reach only a limited number of beneficiaries and are at risk of being captured by local political elites. Participatory selection methods are one of viable and recommended options, although checks and balances must be improved to avoid the possibility of the programme being hijacked for political and patronage purpose. Although a clear and transparent selection process will not guarantee the success of the programme, it will minimize the risk of unintended consequences.

Monitoring, evaluation and learning

Developing a clear theory of change that links programme activities and impact (on participants and society), based on adequate economic, political economy and conflict analysis, is necessary. The common flaw in youth employment for peacebuilding programmes is a weak link between the assumptions made in the theory of change and the indicators in the MEL framework. Adequate peacebuilding indicators are often missing in MEL, which ultimately provides very little information on how the programme is progressing towards assumed goals. It is recommended that programme designers learn what type of peacebuilding indicators have been used, and work, in other programmes implemented in fragile and post-conflict settings and apply them to the MEL framework for youth employment for peacebuilding programmes. Such cross-programme learning can be done, for instance, by incorporating a conflict specialist within the evaluation team or increasing exchanges between different thematic departments. The attribution of intended changes assumed in the theory of change should also be approached more critically by conducting counterfactual thinking analysis, which takes into consideration other possible explanations for this change.

To prove and improve programmes, donors and implementing agencies should encourage learning and adaptive programming. It must be clear from the start what it is that you want to learn from programme implementation and that there is a room to share both good and bad practices. This is also an opportunity to bring youth voices to the fore and to strengthen local institutions that are related to the world of work through multi-stakeholder dialogue. As an increased number of funding agencies encourage learning, working with like-minded partners will facilitate exchanges. Ultimately, an iterative learning processes should be used to contribute to improving practices in general.

Finally, to assess whether the programme actually made a difference, MEL should be conducted a few years after the end of the activities.

These recommendations are based on the synthesis of available evidence on youth employment and peacebuilding programmes in Africa. However, although the specifics may differ, the underlying principles also apply to other regions of the world. Youth employment remains a challenge globally (also in the North) and the programmes addressing it are at risk of being captured for political purposes everywhere. With the latest crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, a number of countries have started funds explicitly targeting youth. These programmes, especially those implemented in fragile settings, run the risk of being used by regimes to strengthen their political position and network. Therefore, funding agencies must be mindful of such a possibility, conduct appropriate risk analysis, and develop appropriate mitigation measures.

[i] Izzi, V. (2020). Promoting decent employment for African youth as a peacebuilding strategy. INCLUDE’s Evidence Synthesis Paper Series no 4/2020. Available at: https://includeplatform.net/publications/promoting-decent-employment-for-african-youth-as-a-peacebuilding-strategy/ ; adopted from Brück, T., Ferguson, N.T.N, Izzi, V. and Stojetz, W. (2016). Jobs Aid Peace: A Review of the Theory and Practice of the Impact of Employment Programs on Peace in Fragile and Conflict-affected Countries. Berlin: International Security and Development Center. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_emp/—emp_ent/—ifp_crisis/documents/publication/wcms_633429.pdf